Prince of Darkness starts out as a film about ideas. In fact, there are too many ideas. Carpenter fixates upon ideas at the expense of creating characters anyone could care about or forming a truly fascinating series of scenes that to integrate the ideas into a plot.

The ideas in the film are jam-packed. The approach is an example of the post-modern technique of narrative that flaunts as much real-world information, esoteric and scientific, high-brow and low-brow, as can be legitimately squeezed into an actual plot. We're given a gnostic Manichean theory, quantum physics, Judeo-Christian mythology, Catholic conspiracy theories, psychokinesis, timetravel involving tachyons, supernovae, computing, ancient languages, manuscripts, mathematics and apocalyptic prophecies.

Yes, this film is smart. Too smart. Much like the novels of Thomas Pynchon, John Barth, and their followers (from Robert Anton Wilson and David Foster Wallace to Neil Gaiman), you're oppressed by a general air of the know-it-all. The characters themselves are all academics, a classicist to analyze the Coptic manuscipt, biochemists to analyze the organic matter, applied physicists to handle the mathematics discovered in the ancient book, computer scientists, and theoretical physicists with highly philosophical inclinations to give naturalistic explanations to properly mythological events.

And there we've come to the crux (pardon the expression). This film, again like the novels of Pynchon et al. functions like an enormous conspiracy theory. A conspiracy theory generally proceeds by amassing data uncritically, taking it all as connected when it ought not to be grouped, and attempting to provide a unifying theory of this data. Scientific theories are successful because scientists accept data critically and group data together in realistic ways. Not so for Victor Wong's theoretical physicist. As far as he's concerned, Judeo-Christian mythology, gnostic dualism, quantum physics and Einsteinian relativity is all legitimate data and should all be explained with a single theory. Since he's not a religious man--and apparently neither is Carpenter, who is also screenwriter--the explanation is naturalistic (i.e. with no appeal to the supernatural).

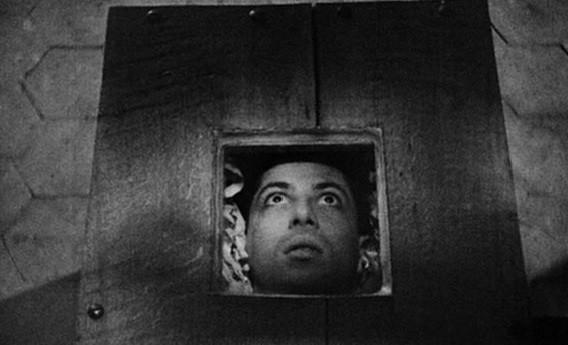

So within the first 30-40 minutes of the film, we're told that all matter in the universe has an opposite, anti-matter; that anti-force seeping into the world is the source of all evil, therefore evil is a physical thing; that both the good and evil sides have a god, which is some sort of alien being; both have a son that came to earth, the good one being Jesus and the evil one being neon green telekinetic liquid called Satan; that Jesus tried to dispose of Satan, but his Apostles decided to hide the information made up some nonsense about evil being in the heart rather than in the world just so no-one could figure out Jesus was an alien warrior come to battle the green liquid; and there's something about logic breaking down at the subatomic level and how this shows our perceptions of time and space are all wrong, all of which is intended to explain away the apparently supernatural events of the film. One oddity is that Carpenter takes the notion of matter having a mirror-opposite so literally he uses mirrors as actual gateways to the anti-world.

Then the film becomes a rather typical possession-based horror film, with a monster, some fights, and a big-bang climax, all of which is rather disappointing insofar as the characters had been largely ignored for the sake of the ideas and then suddenly the ideas are being ignored for the plight of the characters. That just doesn't work.

That's not to say it's a bad movie. Once it gets going, it is actually quite scary; the oppressive music can be thanked for the constant sense of dread. And one character, Walter, does manage to earn the audience--he should have been the main character, not The Mustache. The ideas explored are, moreover, quite fascinating, especially to someone who actually knows a bit about the ideas being played with. As a child watching the film, I had no idea what was going on; now I do, and wish Carpenter had stuck to these guns. At the very least, Carpenter can be applauded for trying to make a genuinely cosmic horror story.

With all of the ideas being thrown around, it's not entirely clear what Carpenter is trying to say. On the one hand, as I think I've already shown, he's not sympathetic to religion, not to its morality or its doctrines. One early shot shows the church and the cross through bars, implying it holds us captive. Other shots show crosses hanging above masses of electronic equipment, implying the co-existence of religious views and science. If anything, it's suggesting science really can explain everything--or at least pseudo-science.

In short, the intellectual build-up never really pays off. One wonders what Peter Weir, or even Nicolas Roeg, could have done with the same material; whatever it is, it'd probably be getting a Criterion release around now.

Moral of the story:

Join the faculty of liberal arts instead.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

Prince of Darkness (1987)

Author: Jared RobertsHouse of Wax (1953)

Author: Jared RobertsI've heard it called a classic with the hearing of the ear, but now I've seen it and know that it's primarily the presence of Vincent Price that makes House of Wax of any interest at all.

Vincent Price plays Mr. Jarrod, an obsessive wax sculptor. He begins by treating his wax figures as people, having invested them with such personality in the creative process, having shared his lifeforce with them, as it were. He is a true creator.

Enter capitalism in the form of a fellow named Burke, who decides the lack of profits from the artsy wax museum warrants its destruction for insurance money. So the wax figures, and Jarrod's face, are melted in Burke's flames.

The creator god becomes a destroyer god: Jarrod, now hideously disfigured both within and without, decides that since pouring life into wax only got him hurt he should reverse the process and start encasing living people in wax. This results in very lifelike figures, but lifeless, dead inside, like Jarrod.

Jarrod himself becomes a sell-out, using his wax figures in lucrative displays of torture scenes in his new museum, including Joan of Ark burning at the stake.

The fiancee of a young sculptor who will be apprenticing with Jarrod discovers Joan of Ark looks too much like her recently murdered friend to be a coincidence, and she pursues this lead to its horrifying conclusion.

Punctuating this action are moments designed to exploit the stereoscopic technology (i.e. 3d!), such as bottles being thrown at the camera mid-fight and a man with a paddle-ball beating the ball virtuosically toward the camera. If capitalism vs. true creativity is the conflictual thrust of the film, we can see which side the creators of this film come down on with this gimmicky 3d.

Ultimately I found the plot of this film to be standard fare, its pacing somewhat mismanaged, the characters uninteresting, and the whole of the proceedings to be mostly unengaging.

There is some good, however. Vincent Price's performance is, as usual, fun in itself. An added bonus is a young Charles Bronson playing Igor, the distinctly hunchback-free mute servant of Jarrod. And the machine Jarrod and Igor use to turn living people into wax figures is itself one of those fantastic, wonky masterpieces of set design American horror films are great for.

The greatest moment of the film is an early chase scene between the disfigured Jarrod and our pretty heroine. This sequence in particular, as well as other parts of this film, is without a doubt a direct inspiration for Mario Bava's superior Baron Blood.

In sum, House of Wax is a mixed bag. Watch for some cheesy, breezy, forgettable entertainment, but don't expect the classic you may have been misled to think you'll be seeing. In double feature with Baron Blood, you may derive some extra enjoyment in noting the similarities.

Categories: 1950s, horror at 9:52 PM 0 comments

Dagon (2001) - 3.5/4

Author: Jared RobertsThere are three collective reasons I can imagine for someone not liking Stuart Gordon's Dagon:

1. Many H.P. Lovecraft fans are obsessive and pedantic about the Master's work, probably due to the esoteric feel one gets from knowing Lovecraft well when so few do.

2. Many think a film should be literally and/or thematically faithful to the literary work(s) it adapts.

3. Many Lovecraft fans thus have a very limited view of what a Lovecraftian film ought to be and reject as a failure any Lovecraft-based film that does not fit the preconceived mould.

And it's mostly going to be Lovecraft fans watching Dagon, an adaptation of The Shadow Over Innsmouth (even though it did not contain Dagon, who is from Lovecraft's story "Dagon"). That alone gets stuck in the craw of the encyclopedic little Lovecraft-buff, and probably hinders his or her enjoyment from the get-go.

I, as it happens, have read very little of Lovecraft and what I have read was read ten years ago. I also happen to think a film has no duty to the work(s) it uses as source material, so even if I had read every word of Lovecraft I'd not judge the film on that basis. Therefore, I have little sympathy for the criteria of judgment the pedantic Lovecraftian indulges in.

With the film itself, we get, from within the first fifteen minutes, almost constant suspenseful action with an hour-long chase punctuated only by a flashback, all set in an exotic, spooky, highly atmospheric location that is perpetually dark and rainy, filled with well-designed monsters that hunt the hero at every step. This is how Resident Evil and Silent Hill should have been done; it reminds one of those games in feeling.

The plot concerns a young man--who has nightmares of a beautiful, black-haired mermaid--his girlfriend, and their two friends finding themselves at the mercy of a mysterious storm. The young man finds himself separated from his three companions in a town populated by fishy (pun intended) inhabitants: human-fish hybrids.

Gradually it is revealed that the inhabitants are worshipers of a being called Dagon. Dagon began by granting the villagers fish and gold from the sea, but soon claimed their souls as they began to mutate into human-hating fish-beasts.

In Dagon Gordon creates a location so evocative and so intensely creepy, it is as if he transposed it directly from his imagination. The labyrinthine Old World town is engulfed in dark, besieged by rain, and filled with fish-mutants with a hunger for our hero. They are everywhere and one never knows where one will come from or what the next one will appear like.

Gordon also creates one of the most suspenseful chases in horror cinema. The entire town pursues our hero as he hides in delapidated buildings, old churches, slimy alleyways. The pursuit continues for nearly the duration of the film. The only period of rest Gordon allows the audience is during an explanatory flashback by an old drunk (Francisco Rabal, no less!).

Needless to say, I found this film to be very impressive. I don't know or care how faithful it is to Lovecraft. Gordon has distilled horror, terror, and atmosphere into an intense, parsimonious 98 minutes of brilliant horror cinema. The images revolt, the monsters terrify, and the dark town overwhelms with atmosphere. I've never seen any other film like it. In fact, the only comparison is what one sees in the imagination while reading some old issues of Weird Tales.

The House in Nightmare Park (1973)

Author: Jared RobertsIt can be somewhat confusing to try to pigeon-hole The House in Nightmare Park. It is ostensibly a horror-comedy--the presence of the great Frankie Howerd telegraphing this loud and clear--but for anyone familiar with Howerd's work, the humour in Nightmare is surprisingly dark. This means the horror receives more accentuation than one might expect. In fact, the film is quite effective as a Gothic horror, borrowing liberally from old dark house mysteries and gialli/slashers (there is a reference to Psycho that's hard to miss).

Frankie Howerd plays Foster Twelvetrees, a music-hall dramatic reader short on luck and talent. Enter Ray Milland as Stewart Henderson, who invites the uncouth moron Twelvetrees to his country mansion as evening entertainment for the whole Henderson family.

The longer Twelvetrees remains in the mansion, the more he discovers that he is at the center of a plot--or several plots--concocted by the thoroughly mad Henderson family, a family of former British-Indian child performers who worship Kali, Goddess of Destruction.

Most of the overt humour of the film derives from how stupid and uninhibited Twelvetrees is and from his animosity with Reginald Henderson. These jokes tend to be hit-and-miss. Some sly references to other horror films should get some laughs from fans. And there is a strain of dark humour as well that does tend to work.

As a horror film, it works much better. Director Peter Sykes is best known perhaps for To the Devil...a Daughter, but has also directed a few other horror films. It by far dominates his oeuvre. Once the action starts, Sykes darkens the house to murk, floods the outdoors with fog, and lets loose on well-paced murders. A snake-pit sequence is particularly suspenseful, despite Howerd's goofiness.

Perhaps the most peculiar thing about Sykes' direction is how visible it is. There are at least a dozen dutch tilts used throughout the film, not to mention some unusual camera angles and even more unusual edits--the most conspicuous of which is a lightning sequence and a dinner-table sequence the breaks the 180-degree rule.

So The House in Nightmare Park is not an unsung masterpiece, though it is quite a good film. It is one that will certainly be appreciated by horror fans, as it is clearly made by someone in the know, bringing a feeling both of Italian Gothic horror (Margheriti) Hammer horror (Fisher) at once. Also, Frankie Howerd fans won't want to miss this; he and Milland deliver great performances.

-

To top off this review, here's a clip from a truly bizarre and hilarious sequence from the film: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3JH2pK07vTE

You've never seen Ray Milland like this before.

The Stuff (1985)

Author: Jared RobertsLarry Cohen's The Stuff is a The Blob-style horror-thriller combined with the stylistic approach of 70s Romero and the whimsical satire of SCTV. Were The Stuff the sum of its influences, it would be a masterpiece; though it is no masterpiece, it succeeds as a horror film and is amusing, if uninsightful, as a satire of consumerism.

The plot involves a white substances that bubbles up from a hole in the ground behind a factory. A man tasting it discovers it's delicious. Soon it's being marketed as a dessert product called "The Stuff" with enough commercial clout to rival Pepsi. Unfortunately it addicts its consumers, eats out their insides, and renders them host shells for the stuff.

Meanwhile, a cohort of businessmen arrange to have industrial saboteur named Mo ('cause when he gets money, he always asks for mo'--he reminds you of this every few minutes) investigate The Stuff. A little boy escapes from his stuff-infected parents. The marketing genius behind The Stuff disaffects and falls in love with Mo. And a ruined dessert CEO, Chocolate Chip Charley, fights the minions of the new industrial superpower. Somehow all of these characters meet up and find their lives frequently threatened by The Stuff and its host bodies. A bizarre, retired colonel who lives in a castle joins the fight later in the film.

Stylistically, the film is much like Romero's The Crazies, but not nearly so serious. It has a gritty, realistic feel, a constant sneer of disdain about certain conduct within society, and a seemingly unstoppable menace that takes over once-normal bodies.

Where these films differ is that Romero seems to be putting real institutions and real people in a petri dish and under a microscope. Cohen, on the other hand, has a certain college boy facetiousness, as if he were saying this is what probably would happen if a dessert product bubbled out of the soul--and we can all have a laugh over it.

Consequently, Cohen's film isn't as strong as Romero's. His dialogue is frequently throw-away, utilitarian, or just preposterous. While being chased by the minions of The Stuff, Mo and Charley take time to make casual witty comments before trying to get away, for instance. Some characters seem to have come from outer space, like Paul Sorvino's colonel. The little boy seems remarkably unperturbed by having lost his whole family. Other hints suggest that we are not dealing so much with real people as with action figures to carry along the message.

The message is as hamfisted as Romero's messages. It is perhaps even more cynical--or realistic you may say. However, it is presented with more wit and verve. The Stuff is a mirror for megaproducts like Pepsi. The advertising campaign resembles some cheesier attempts at marketing Pepsi and Coke (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=va7bjHYCIGI). The way The Stuff effects an Invasion of the Body Snatchers sort of program is certainly a comment on the way marketing takes away one's freedom to think critically about products--the conformism of the marketed world. And the actual CEO we meet towards the end of the film and what is done to him is as clear a statement as it gets.

However, The Stuff is a very entertaining film. It actually delivers on scares, particularly in the scenes where the little boy is in trouble. The special effects for the stuff itself are fascinating and effective. It's also quite a funny film, even if the satire is the same anti-consumerism you've seen many times before. The zaniness of the characters won't distract at all; they fit, because they're the closest to sanity in a 'world gone mad'.

The Flesh and Blood Show (1972)

Author: Jared RobertsDirector Pete Walker, a sort of horror auteur insofar as he owned the production company, began as a director of nudies and rougies. Although later renowned for the blood rather than the flesh, The Flesh and Blood Show is one of his earlier horror films and as such shows off the flesh much more than the blood.

That might be something to complain about were the sex not so integral to the horror and plot. Much like Bava's Bay of Blood, The Flesh and Blood Show is a prototype bodycount slasher; also like Bava's Bay of Blood, it is superior to most of its followers. Where all slashers have an occult link between the sex and the violence, The Flesh and Blood Show provides a very clear, causal link between sex and violence that I shouldn't reveal.

Also like a slasher, The Flesh and Blood Show is peopled primarily by attractive youths plopped together in a camp-like situation. In this case, they are theater students improvising a show, and they are camping out in the old, abandoned theater as they reason it will be easier on their budgets.

However, it would be a mistake to assume they're all oversexed, stupid teens. In fact, they're not teens and there's considerable variety in their attitudes towards sex. Mike, the leader of the group, is only interested in getting work done. A handsome Australian--handsome enough that he's probably never gone a week without a 'piece of tail' since he was 15--quickly shacks up with an aggressively horny blond. A sexually frustrated prankster broods over their relationship and generally raises suspicions. And an experienced lesbian takes advantage of a more innocent young lady.

Were this a traditional slasher there would be only two characters here really deserving of the knife. In this film, the killer makes the assumption we might make coming into a slasher: these are young people camping in a theater; so they're probably all sexually loose hippies. Thus the bodycount mounts while police are led on wild goose chases, leaving the actors vulnerable.

The film is generous enough to delve into the killer's psychology and show us that the motive is indeed sexual prudery of sorts--combined, perhaps, with sexual perversion. This generosity involves, of all things, a sudden performance of Othello at the climax of the film.

It's all handled with enough ambiguity and cleverness to keep one thinking some after viewing, maybe even enough to get a rewatch. It's also exploitative enough to keep sleaze-hounds entertained, with some nice tits on display. On a technical level, the film is professionally manned behind camera, and the actors are above average, especially for this sort of film. And British cinema fans will want to keep an eye out for Robin Askwith in a pre-Confessions and pre-Queen Kong role.