Several vampire films made in the late Seventies and early Eighties challenged the tropes and conventions of the vampire film. The Gothicism of Hammer's vampire films, even the modernized and gleefully exploitational The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973), had become too formulaic to continue affecting audiences. Polanski's Dance of the Vampires (1967), however critically derided, essentially put the stake in the heart of the Gothic vampire film. Al Adamson's Blood of Dracula's Castle (1969) with its comically effete Dracula continued the progress of Gothic vampire films into camp. The level of camp to which the Gothic vampire film had developed is exemplarized in the August Rieger-penned The Vampire Happening (1971). For better or worse it lives up to its tagline, "The Adult Vampire Sex Comedy!" Fleeing Gothicism and its supernaturalism, a new school of filmmakers, nearly all with recourse to science, brought realism to the vampire subgenre. Moctezuma's Mary, Mary, Bloody Mary (1975) depicts vampirism as a biological mutation causing the overdevelopment of blood vessels. The only way to keep the rapidly-expanding blood vessels filled is to drink blood. It's not good science, but it's a valiant effort. Vampirism is the result of a parasitic implant designed by medical science in David Cronenberg's Rabid (1977). Colin Wilson's novel Space Vampires (1976), adapted by Tobe Hooper as Lifeforce (1985), depicts vampires as energy-sucking extraterrestrials. Somewhat an epigone but still worthy of mention is Kathryn Bigelow's Near Dark (1987), in which vampirism can be cured via blood transfusion. The exception is George Romero's masterpiece Martin (1977). Romero employs neither science nor the supernatural, relishing the ambiguity of Martin's ontological status, hence refusing us any epistemological system that might yield solid answers. This makes Martin easily the most radically challenging of all these radical vampire films. Finally in the mid-Eighties when filmmakers began to integrate Gothic tropes into modern settings, a Hegelian synthesis of sorts, the best instance of which is probably Fright Night (1985), this period of the radical vampire film came to an end.

Thirst (1979) was created in the middle of this trend. In many ways Thirst is the most radical of them all, even more so than Martin. Thirst concerns a vampire society administration's efforts to convince the oblivious Kate Davis (Chantal Contouri) that she is truly a vampire. Kate is a normal, modern, and very successful woman. She owns a fashion design company. She sees a handsome architect exactly three times every week. Her life is organized on her own terms. We know all this because a vampire private investigator reports this information to his superiors, Drs. Fraser (David Hemmings) and Gauss (Henry Silva) and Mrs. Barker (Shirley Cameron). They believe Kate is descended from the noble vampire lineage of Countess Elizabeth Bathory. Without Kate's knowledge, they not only plan to bring her into their community, effectively ending the lifestyle she now enjoys, but have also arranged her marriage to another descendent of a noble vampire family (Max Phipps). As such, Thirst is structured more as a psychological drama than as a vampire film. The final question becomes not whether the vampires will be staked or whether they will bite her, but whether Kate will acquiesce to her vampiric destiny or whether she will assert her independence and humanity.

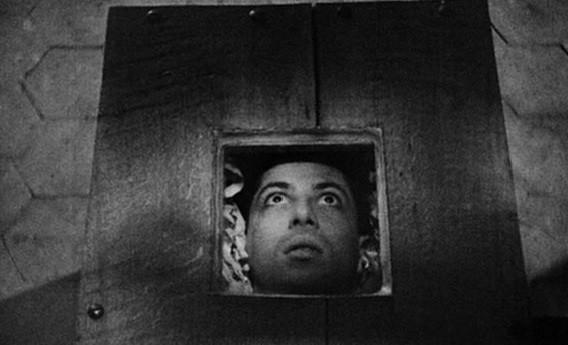

The way Kate becomes a political pawn within the vampire community is one of Thirst's most interesting and innovative features. Her conversion to vampirism becomes the Ace of Spades, so to speak, for the three administrators of the vampire community. Her noble lineage and arranged marriage implies favour with the noble families for whomever successfully accomplishes Kate's conversion. The vampires try various means to arouse in Kate 'the thirst'. In this sense, Thirst plays somewhat like Dracula's Daughter in reverse. Kate doesn't hear 'Dracula's call' or 'the thirst,' but others want to make her do so. Dr. Fraser is a sort of Toranaga, treating Kate kindly and with respect, trying to reason her into the community, all the while aware that she's the key to securing his position as director of the facility. Mrs. Barker, on the other hand, is a cruel and results-driven mad scientist, willing to use brainwashing techniques resembling those employed by the No. 2s of Patrick McGoohan's The Prisoner should Kate put up any resistance, in order to usurp Dr. Fraser's position.

Vampires traditionally have certain features that remain present even in most of the radical vampire films. Vampirism itself is nearly always taken to be an evil in the Augustinian sense of a negation: It sets the vampire against all that is considered good beyond the bare minimum of continued existence. While vampires can put on a veneer of civility for the sake of acquiring victims, as Bela Lugosi's Dracula does, the vampire within is ultimately a savage beast: it is without reason, civility, or love; it is appetitive, predatory, and profoundly alone. Dracula's Daughter (1936) explores this to some degree in that Countess Zaleska (Dracula's daughter) struggles to be a part of society, to find love, to resist the vampiric urges she refers to as 'Dracula's call'. She fails. This solitary and destructive quality of the vampire persists throughout Mary, Mary, Bloody Mary, which follows but modernizes the model of Dracula's Daughter, Rabid and even Martin. What makes Thirst so radical is that its vampires are reasonable, civilized people who live together on communes as well as all over the world in human society. The only prior instances of vampire civilization are in the camp films Dance of the Vampires and The Vampire Happening and, the sole serious instance, The Vampires' Night Orgy (1973). Thirst is the first film to realistically depict a vampire society, with internal, political struggles. They're ordinary people. So ordinary that they cease to be monsters. So ordinary that the question of staking them never arises as a potential resolution. So ordinary, in fact, that, should 'the thirst' not be aroused, they can go through life never even realizing they're vampires, raising the ontological question first raised in Martin as to whether they're vampires at all and not merely a secret society of deluded people.

The ontological ambiguity of the vampires in Thirst is a direct consequence of its science. Not only is Thirst the most radical of the radical vampire films, it is also the most radically scientific. Where Cronenberg's vampire in Rabid is an instance of benevolent medical science gone wrong, the vampires in Thirst are in some sense a construct of science that is sustained by scientific activity, not merely physically but even conceptually. In Laboratory Life: The Social Construction of Scientific Facts (1979) Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar, based on time spent studying scientists as anthropologists would any culture, argue that scientific facts as basic as the existence of the electron are as socially-constructed as myths. The electron's existence was not observed, but began as a speculative statement in order to explain abstract data. The machinery that is constructed to measure the electron is already determined to recognize the facticity of the electron. That the machinery will work is thus already decided by the design of the machinery to yield results favourable to the existence of the electron. Yet the results of the machinery is taken to support the facticity of the electron. The fact of the electron is therefore created in the minds of the scientists and their instruments of measurement.

I don't care to defend the theories of Latour and Woolgar in real life instances. They do, however, enlighten the way science works in Thirst. The vampires have a vast system of highly-developed machinery predicated on the notion that these people are indeed vampires. Yet the whole machinery, social and technological, is taken to simultaneously prove they are vampires. The commune itself is referred to as a 'dairy' where blood is 'milked' by sophisticated equipment from 'blood cows,' also known as humans. The purpose of doing so is perhaps to eliminate the need for predatorial activity, but mostly, as is explicitly stated in the film, to do away with dangerous impurities in the consumption of blood. So the dairy is predicated upon vampirism and the main concept of vampirism, "the thirst." At the same time, the inferiority of these 'blood cows,' their docility and apparent contentment at serving in the commune, is taken to prove that the "vampires" are really a superior race and not just humans. As one character states, drinking blood is "the ultimate aristocratic act."

More importantly, the existence of the 'thirst' itself is dubious. Mrs. Barker employs a series of brainwashing techniques, or what she calls 'conditioning,' in order to arouse the thirst in Kate. That it takes Kate so long to realize she has the thirst is attributed to Kate's being strong-willed. When Kate finally begins to exhibit some signs of the thirst, the machinery is believed to have been effective in arousing the thirst. But isn't it a more reasonable interpretation that the thirst was merely created by extensive brainwashing as a result of highly-sophisticated equipment and systematic injections with a mollifying serum? Like the electron in Latour's theory, the thirst here seems to be a fact only within the minds of the vampires and in their instruments. One could just as easily adopt the alternative interpretation. It would be too costly for them to deny the existence of the thirst, however. The thirst is the central proof these people have of their vampirism and with the superiority that entitles them to be vampiric. They use sharpened dentures as they don't have fangs. Though their eyes appear to glow red, this may or may not be an effect of contact lenses. It's left unclear in the film. It is only the thirst the makes the vampirism and all its paraphernalia authentic. Their existence as vampires depends upon belief in the thirst. And the thirst's facticity appears to be socially-constructed. Consequently, the vampire is purely a scientific construct and upon the ambiguous facticity of that construct rests the ambiguity of the vampires' ontological status.

I discuss the science in Thirst at length not only to describe the tenuous reality of vampires in the film, but also because science is integral to the film's horror. It is in its radical way as much a mad scientist film as it is a vampire film. Pinkney's screenplay reflects the late-Seventies' paranoia over the dehumanizing aspects of sciences that demystify the biological and psychological aspects of humanity. In the scientific community of the vampires the only options are to lose one's humanity to vampirism or to adopt the bare minimum humanity of the blood cows. Perhaps it's not a coincidence that Kate is involved in fashion and her boyfriend is an architect. Both are involved in the arts and live fulfilled human lives, free lives. Under the gaze of the scientific community, they must be either vampire or blood cow. The scientific community orders everything rigidly, including genetics (arranged marriage), permitting only illusory freedom. The blood cows are not free to leave. So lacking in blood are they that they behave as though lobotomized. And the vampires are slaves to their own science: the thirst and the machinery. If horror films are nightmares that present us with the social and personal desires we repress, perhaps the horror of this scientific order is because we on some level desire it but have a still stronger desire to repress it, just as Kate as a capitalist in some sense desires to have her financial superiority biologically confirmed and yet fears such a visceral acknowledgment.

On another level, the whole film is structured as a way of 'breaking' a strong-willed, modern, independent woman. Thirst is, after all, Kate's nightmare. Her everyday life is subverted by intrusion from a patriarchal community. They have determined that she's valuable to them for her genetics, in other words, for her reproductive merits. Instead of being valued as a mind, she's valued as a womb. Her mind is manipulated cruelly to make her a willing womb. On the other hand, the males in the film are strangely effeminate and gentle, the women strong and results-driven. Kate's arranged husband is a bundle of nerves who requires brainwashing to get the strong Kate as his wife. Derek the architect sees Kate on her terms. In the vampire hierarchy, Dr. Fraser is gentle, albeit a commanding presence. Mrs. Barker, however, is assertive and dominating. There's no question, though, that Dr. Fraser is presented in a much more sympathetic light than Mrs. Barker. So perhaps Thirst is not just a nightmare of dehumanization, but a nightmare for female independence: a perversely cathartic vision of the rising female independence threatened of destruction by a highly intelligent male force. Since humanity and this independence are co-extensive terms in the nightmare of Thirst, this vision is at least treated as an equally perverse desire and one that is to be repressed.

Thirst is not the work of art that Martin is nor the philosohpical excursion Rabid is. It is an Australian exploitation film lifted by an efficient director (Rod Hardy), a daring producer of the Australian New Wave (Anthony I. Ginnane) and a strange and original script from one-timer John Pinkney into its unique radicalism. Both highly idiosyncratic and a product of its cultural and cinematic milieu, Thirst is in many ways the ultimate Seventies vampire film as well as one of the most original vampire films ever made.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

A Classic: Thirst (1979) - n/r

Author: Jared RobertsBlood Night: The Legend of Mary Hatchet (2009) - 2/4

Author: Jared RobertsBlood Night may just give The Legend of Hell House a run for its proverbial money in the bathetic motive department. The climax of Hell House reveals that the eldritch horrors have been unleashed by a severe case of Little Man Syndrome. Blood Night reveals from the beginning that a horrendous mass murder and a possible haunting were both triggered by menstruation. When little Mary Mattock had her first period, she brutally murdered her parents. Locked away for a decade, raped by a night guard, impregnated, and parted from her child, her next period triggers a mass murder in the asylum resulting in many a decapitation and her death. Hence Blood Night, the in-film unofficial holiday that celebrates the bloodbath Mary Mattock wrought as well as the bloody cause of her insanity. Of course, during a Blood Night celebration, killings begin again. Silly as it may seem, there have actually been documented cases of menstruation-induced homicide (e.g. Sandie Craddock). But it's a particularly strong menstrual cycle that reaches out from beyond the grave.

What's most interesting about Blood Night is the unique culture it creates for its small town with the Blood Night legend. The eight-minute pre-credits sequence very economically gives the entire Mary Hatchet story. A series of newspaper clippings during the credits reveals how Blood Night developed out of Mary Mattock's story. It's a town-condemned phenomenon amongst the local youth, partially an opportunity for widespread mischief, partially an excuse for drunken parties, and partially a cover for indulgence in the macabre. Most of all it's a means of dealing with a traumatic event. Just as individuals find means, which are frequently unhealthy, of dealing with trauma, so do communities. Where adults employ rituals of solemnity, youths tend to employ irreverence, trivializing traumatic events with silly songs, stories, games, and so forth. In Blood Night the irreverence consists in visits to the cemetery, Mary masks, pranks, jokes and parties. Writer-director Frank Sabatella's finest touch is to show an online Flash game based on Mary Hatchet. Marys pop up from behind headstones throwing axes and the player stops the Marys by throwing tampons. It's just the sort of facetious game that would be made from such a legend. Adults are often disdainful of the way youths deal with trauma; but solemn rituals or playful rituals are both still rituals, still a response to the trauma by means of repetition. However we may perceive the playful rituals as disrespectful, they have the same repressive effect as the solemn ones.

In the milieu of Blood Night a group of high school seniors led by Alex (Nate Dushku) take a ouija board to Mary's grave. Creeped out by the stories of cemetery keeper Graveyard Gus (Bill Moseley) and the planchette's apparent uncaused motion, they wind down at a house party with drinking, jokes, and sex. Then the heads start to roll. This is a very interesting structure; I can't recall seeing that exact structure in horror before: the tongue-in-cheek celebration of a traumatic legend is transformed into a horrific re-enactment of the original trauma. In one scene a girl tells a harrowing story that ends in a punchline. In some sense the opposite is being inflicted on these teens. For treating the traumatic event as a punchline, they're being inflicted with the trauma. Their attempts to repress the trauma with mirth has ultimately been transformed into its return. Nevertheless, the structure isn't outside of tradition. Mario Bava's films, especially the masterpiece Black Sunday, are often structured around a legend of some traumatic event. The structure can be found in films as diverse as Pete Walker's slasher The Flesh and Blood Show and the family-friendly Hocus Pocus. Someone somehow aggitates the original and dormant trauma, causing its return. In Black Sunday Asa is revived by the accidental spill of blood. Suddenly the town and family that have tried to forget her are placed face to face with the original horror. In the context of the story this is an evidently bad thing as deaths result. On a holistic level, however, it's very good: The trauma's return is the opportunity to face it head on and destroy it once and for all. Usually the one who disturbs and leads to the trauma's destruction is an outside influence, like the doctors in Black Sunday. Sometimes, as in Hocus Pocus, it's a local. The outside intervention tends to support the need for assistance, perhaps even indicating the role of a therapist. When the resolution of the trauma is the work of a local, the message is usually one of self-sufficiency and independence. Either way, the trauma, as in Blood Night, is never over until it has been confronted.

The trip to the cemetery and the use of the ouija board are standards in the structure of trauma-aggitation. Many horror films, especially haunted house films, are structured around an original trauma. Ouija boards and séances are frequent causes of the return of the trauma. They aggitate it and cause it to resurfance. In Mario Bava's Gli orrori del castello di Norimberga an incantation resurrects the legendary sadist Baron Blood, for instance. In Blood Night it's not so clear that the ouija board works. The film skirts around and plays with supenaturalism, but undercuts its own structure with the anxiety of female sexuality. It is not so much the ouija board as the mounting eroticism of the party, during which a porn movie is shown and multiple couples go off to bedrooms, that aggitates the trauma. Menstruation and pregnancy take the thematic place of conjuration and necromancy. Mary's menstrual rage in the pre-credits sequence gives her superhuman strength sufficient to decapitate victims seemingly without a weapon. She targets both men and women. Yet Blood Night undeniably expresses an anxiety about the unique powers of female sexuality, the capacity to bear children and the millennia of mysticism surrounding female fertility. This is a feature Blood Night shares with Ginger Snaps or in an inverse way with Valerie and Her Week of Wonders. In Ginger Snaps budding female sexuality becomes really and allegorically lycanthropy. Valerie is a more subtle case, where Valerie's first period invites a bewildering train of psychosexual terrors in the form of vampirism. All of these films show the anxiety men have been expressing since the Pandora's Box myth. Most interestingly, characters themselves in Blood Night are mistakenly convinced they're in a standard trauma-aggitation structure as they team up with Graveyard Gus to try appease the spirit of Mary.

The collision of these two structures is fascinating to see, as is the characters' own confusion about which structure they're in. However, it doesn't necessarily produce an entertaining horror film. The first ten minutes of Blood Night are highly economical, setting a high bar for the rest of the movie that it doesn't quite meet. Post-credits, we're immersed in several dialogue-heavy scenes of teenage banter and storytelling until the middle of the movie. When violence does start, it seems too fast and too disordered. A lot of characters have been set up at this party and many of them are decapitated in a short time. The transition from levity to brutality left no development. There is no emotional engagement with either terror or horror. The climax is a chase sequence in which the victims disperse and the axe-wielding maniac stalks each individually until a select few remain. There's very little in the way of tension or suspense even during this scene. Sabatella is more interested in the resulting gore effects than the build-up. Perhaps it's not surprising for a film so afraid of female sexuality that the climax is preferred to the foreplay.

Speaking of gore, Blood Night makes the mistake a good many low-budget horror films make. Zombie films make this mistake more than any others, but slashers like Blood Night come second. The mistake is focusing on the gore. Gore is more effective when glimpsed rather than scanned. Compare the ridiculous scene of spider's ripping latex flesh in Fulci's The House by the Cemetery with the machete-to-the-skull in Cannibal Ferox. Ferox is much more effective. I can think of a few reasons. For one, when we focus on the gore, we the audience have time to rationalize it and detect its flaws, to say to ourselves, "It's just latex." Moreover, the natural response to disgusting images is to look away. If the camera is an extension of the audience's eyes into the film work, the unnaturalness of the camera's obsession with gore makes us suspect: we wouldn't focus on it so were it real! A film like Cannibal Ferox shows the gore-event in a second and quickly cuts to a horrified woman captive looking away. Gore effects are, paradoxically, more effective the less they are shown. Blood Night shows the neck stumps of beheaded victims and their rolling heads far more than it should.

One of Blood Night's major pulls for genre fans will be its two Horror Stars, Bill Moseley and Danielle Harris (of Halloween IV and V fame). Moseley has always distinguished himself by putting his all into a performance, no matter how vapid the material. In Blood Night he has been cheated of any interesting dialogue, alas. He is given a ghost story that is intended to sustain a sense of menace, but it doesn't work. Harris is also given a story of a lighter tone and it consequently works better. Her fans may be pleased with how her role develops. Curiously enough supporting actor Billy Magnussen steals every scene he's in as Eric, the fun and friendly party guy. Hopefully this won't be Magnussen's last foray into the genre.

Ultimately Blood Night is just too scattered in tone and ideas, never quite concluding anything. Its strength is in the perverse small town customs it builds up around the Mary Hatchet legend and the people who celebrate it. Unfortunately the plot takes over and takes these people down the pathway of ineffectual gore and violence, rushing toward an artificial set of conclusions.

Categories: 2009, horror, slasher Tuesday, April 20, 2010 | at 12:25 AM 0 comments

Finale (2009) - 3/4

Author: Jared RobertsYou can always tell a movie has good writing when it resists that temptation for immediate explanation that is called 'spoon-feeding.' Some movies have this imperative to explain. They need to stuff the answers into the audience immediately, lest the audience be lost for even a moment. John Michael Elfers, who wrote and directed Finale, never forces the exposition. He so trusts the audience to endure the temporary confusion and to make the necessary connections when finally he enlightens us that he allows the mysteries to linger until near the film's end. The first ten minutes are very confusing, but the patient viewer will be rewarded. Confusion is not necessarily a bad thing. Finale is partially about confusion. It concerns the confusion of a family in the aftermath of an apparent suicide. As the family members, especially the mother, are thrust into confusion, it's important that we're confused with them. This puts Finale in the tradition of two other great confusion movies, The Seventh Victim and Rosemary's Baby. And not coincidentally, all three films are about satanic cults and families.

Satanic cult films tend toward two poles. There's the realist pole. The Seventh Victim, Race with the Devil and Rosemary's Baby are satanic cult films of the realist variety. The cult is represented as a rather ordinary, even pathetic, collection of humans with no obvious powers. In The Seventh Victim the cult appears more like a resentful upper-class clique than a cult in contact with supernatural evil. Their forces are purely physical (the assassin) and psychological (urging to suicide). Rosemary's Baby has some ambiguity. We're not certain how much Rosemary imagines and how much is real. There may well be a cult, but there may not be any supernatural forces at work. The characteristic feature of the realistic satanic cult film is paranoia and confusion. Paranoia because there is no way to know a cult member from a non-member, confusion because there is no way to know a part of the conspiracy from an ordinary event. There is, on the opposite end of the spectrum, the supernaturalist pole. Night of the Demon, The Devil's Rain and The Devil Rides Out are satanic cult films of the supernaturalist variety. In all three films we're unambiguously treated to horned demons, powerful magic and horrific apparitions. Instead of paranoia, these films create a sense of vulnerability. The Devil Rides Out especially plays on vulnerability as it climaxes with the protagonists huddling in a small magic circle.

Finale falls in between the poles, much like Polanski's The Ninth Gate. As in The Ninth Gate, there is a real supernatural evil at work. As in The Ninth Gate, the satanic cult is an ordinary yet dangerous collection of real people. As in The Ninth Gate, Finale creates a sense of both paranoia and vulnerability as mysterious forces natural and supernatural impose upon the protagonist. The vulnerable target of the cult in Finale is a Catholic family, the Michaels, consisting of a mom, a dad, and three children. The authorities conclude the eldest son Sean has committed suicide, but his mother Helen (Carolyn Hauck) is not convinced. As she investigates Sean's strange behaviour before his death, she finds he had uncovered a cult's secrets and was terrified of the demon they control. Helen becomes increasingly paranoid and worries for her now vulnerable family, especially her teen daughter Kathryn (Suthi Picotte), whose involvement in a drama club may have put her in the cult's hands. Unfortunately, her family thinks she's just having a breakdown.

Helen herself is a fascinating character. She's the center of the paranoia, the Rosemary of this film. Hauck plays Helen manically, lending the film that same sense of urgency found in Rosemary's Baby. One really feels time is running out and it's Hauck's performance that centers the feeling. But where it took Rosemary to the middle of the film to realize she has to do something, Helen realizes this near the beginning and the urgency mounts to the final moment. Also like Rosemary, Helen's a psychologically soft person to begin with, making it easy to distrust her. She has somnambulistic episodes as she dreams of interacting with her dead son. She is, after all, a Catholic; if her son committed suicide, his soul is lost. Since we're permitted to see her episodes subjectively, in some lyrical dream sequences. This leaves open the possibility that she's just paranoid and that the denial she's suffering over her son's death has led her to concoct a satanic cult conspiracy. At least, that's how it should feel for the audience. Elfers seemingly gives away the real presence of a cult and its supernatural powers in the first five minutes, reducing the potential ambiguity. But it isn't impossible to see those five minutes as a vision of Helen's. Elfers uses a hermetic editing style that permits this interpretation.

Both Elfers's narrative and his editing style give the film a hermetic quality. Everything seems linked to everything else. Nothing appears to happen by chance. A chat with a priest, a drama club, teenage romance, the satanic cult, pipe bombs, an abandoned factory and a cat woman all somehow connect. As in any conspiracy theory, nothing's allowed to be extraneous. The editing style similarly makes confusing connections we must wait to understand. For instance, when Helen's living son tells her, "Mom, I want to talk to you about something," Elfers cuts to a shot of a burning house, breaking the unities of both time and space. The significance of that shot doesn't become clear until the end of the third act. The confusion this generated on first viewing immersed me in the paranoia; I felt the conspiracy. Elfers makes everything feel connected with his editing, even if you don't know why it's connected. Perhaps we're immersed in Helen's psychological torment and feel with her the urgency to make sense of all this material.

The apparent Catholic ideology of the film may support this view as well. Nearly every character in the film is ostensibly Catholic. During her drama audition, Kathryn has a self-written soliloquy about the horror behind the figurative masks people wear. There are those in the film who are willing to sacrifice themselves for loved ones and those who sacrifice loved ones to the demon for their own gain. Kathryn's soliloquy, which references God directly, is thus about who are the true Christians. The apparent Catholics who actually pray to a demon for selfish desires are allegorical of those who believe on the surface but fail to show Christian charity. Now we can return to Helen. The whole film is Helen's struggle to protect her family from this demon called 'The Collector', so called because it 'collects' souls. Her efforts transcend merely protecting her living family to redeeming the soul of her dead son. If in her mind the demon is symbolic of separation from God, her willingness to sacrifice her life to stop the demon is a symbolic Christlike redemption of her son. The Catholic ideology doesn't work quite as well if what we see is taken literally, because the Christian belief system only allows the loss of the soul by free will. A demon can't just take your soul. The Catholic allegory falls apart anyway when the explosives and knife-fights begin. Although, there is something eschatologically valid about the destruction of 'false Christians' in an inferno.

I've been praising Elfers's willingness to leave points unexplained and the audience in confusion. However, some areas are under-written. Particularly the demon and the cult. In The Seventh Victim we know what the cult wants and why. In Night of the Demon we understand the rules of the game, what Karswell can and can't do, and how the demon will come. We do get a set of rules on how the demon functions, such as the exact minute it can attack, but not a clever means of getting rid of it. The game of wits from Night of the Demon is reduced to blowing the cultists to smithereens here. But it's not clear what the satanic cult in Finale is all about. The demon seems to have one function: killing for souls. But why do these people want the demon to kill so often? These people function normally in society, so they can't have that many enemies. It's not clear why they resent the whole Michaels family so much either. Is it simply because they're Catholic? Not knowing whether Elfers is himself Catholic or not, all I can say is Finale seems to express a general paranoia about the position of Catholics in a secular world that increasingly villainizes religion and that increasingly encourages self-interested behaviour.

Then there's the appearance of the demon. Tourneur loathed having to show the demon at all in Night of the Demon, but the demon they settled on is indeed a fierce-looking beast. Elfers's demon is relying on his visual style. His style is made up of peculiar optical tricks, such as creative use of lens flares and gels. It gives the film a heavily-processed look, not unlike Saint-Booth's Death Tunnel. The IMDb trivia assures me that Elfers's visual trickery was all accomplished in-camera. If that's true, it's very impressive. But the effect is still similar, regardless of the cause. In many instances it's elegant, such as a horrific suicide scene and the orgiastic demon-summoning. In other instances, it's not so effective: the demon itself is a wiggling bald man in a strait jacket shot through a blue gel, soft-focus and sped-up. It doesn't quite have the menace a soul-stealing demon ought to. Its only means of attack is to telekinetically strangle through mirrors. So it has no actual contact with the actors. It's a valiant effort at minimalist demon-construction, but not very frightening.

But then, The Seventh Victim isn't frightening either. Finale, like The Seventh Victim, creates more of an existential terror, in this case from a Catholic existentialism. And both films anchor that existential terror in atmospheric set pieces, which are really Finale's biggest strength. Helen's dream sequences always show her with flowing lace trains navigating familiar sets given an uncanny feel with wind and well-chosen camera angles; the spaces have a desolation that perhaps mirror her inner turmoil over her lost son. A chase through an abandoned factory beside a cemetery is poetically nightmarish and one of the best chases I've seen in a recent independent horror picture. Helen might as well have been pursued by doubt itself.

Elfers packs a lot of narrative into Finale's ninety-minute runtime, making the comparison to Val Lewton's masterpiece The Seventh Victim a legitimate one. Both films move across a lot of narrative material, over shocking and potent moments swiftly, leaving even the attentive viewer a little behind on all levels. The full impact or significance of some moments don't quite register until one takes the time to reflect or rewatch. While not as delicately constructed as The Seventh Victim or as subtly manipulative as Rosemary's Baby, Finale is a good entry in the tradition of satanic cult pictures.

Categories: 2009, horror, supernatural Friday, April 16, 2010 | at 10:57 PM 0 comments

Madness (2010) - 3/4

Author: Jared RobertsMadness is a particular kind of horror film that has direct roots in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. In the post-millennial era this particular horror film structure has become even more popular. I could tell Madness is this kind of horror film when the gas station appears in the first ten minutes of the film. At that moment I knew something creepy would happen at the gas station. I knew that the traveling protagonists would ignore the creepy event. I knew that they would run into a band of dangerous backwoods folk and some of them would die. I was correct in all these assumptions.

The foundation of this horror structure is the presumed autonomy of the travelers. In this case it is two young women. Usually the travelers are young, as youth is the age when we usually strive to express autonomy through adventure. The travelers get together and go on a road trip. They are totally free to chart out their own path in the world. They usually have a destination, but it is a destination of their choice. They choose their destiny. It never occurs to them that the world is not as pleased about their freedom as they are. They take for granted that the world is a safe place, that the rest of the world is similar to their home. These films are structured to punish this autonomy. The sense of security and freedom in the world that permits these young people to leave the 'nest' of their hometown and make their own destiny is destroyed. The destruction of security is always performed by an embodiment of savagery. In Christian-era folk stories, the vessel of danger is usually a pagan, as in Hansel and Gretel. Pagans were the perfect vessel for embodying all that is opposed to civilization, such as the security and freedom laws and morality ensure, because they were the people deemed spiritually backward in a spiritual society. In a socio-political society like ours the embodying vessel of anti-civilization is a socio-politically backward people, such as Nazis (Frontière(s)) or rednecks (The Hills Have Eyes, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre).

The presence of the gas station is thus highly significant. If the road and the car connote autonomy, then the gas station is a moment of dependence on society. Total independence from other people is not possible. The gas station scene always includes a warning of some sort. A local warns the youths not to go where they're planning to go or some creepy or startling event suggests there may be danger ahead. The gas station thus forms the bridge between venturing-too-far and thereby becoming lost-in-the-woods and a legitimate exercise of autonomy. The gas station is the moment the characters can realize that they've gone too far and must return home. They invariably never do return home and they are consequently punished for their wanderlust. The message of these films, then, is always that the wanderers should have been content to stay home. It's a dangerous place outside of home. More abstractly, these films also warn against excessive independence, particularly the independence found in choosing one's own destiny. Overstepping the bounds of personal freedom posits the individual outside of a sphere of security. Even in those films where a victim survives the ordeal, one wonders how that person will ever be able to leave her house again. She's seen and now she knows that it's a dangerous place out there, both physically (away from home) and psychologically (excess independence).

This structure receives its crystalization with Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. It is a peculiarly American structure. In the Hansel and Gretel tale the children are sent from home. This is also true with Little Red Riding Hood. The traditional fairy tales with similar structures therefore aren't about autonomy expressed through travel. There is also a component of travel-unto-horror in films like The Old Dark House. But the Femm family is more civilized than their guests. That's a major point of The Old Dark House. The focus is on the decadent civilization rather than the travelers' freedom. It is only in the midst of the '70s, with the explosion of freedom in the USA, that the travel-punish structure arises. This is indeed odd for a nation that values independence so strongly. It is as though Americans have a need to see their urge for independence and autonomy punished on screen. Or perhaps, more subtly, the need is to see their own urge to punish autonomy cathartically presented and dealt with in the film, so they might return to being good Americans with their urges to enforce conformity repressed. There is also a spiritual aspect to this structure. America is unofficially a Christian country. But the total freedom to choose one's own destiny is a secular, humanist, or even existentialist notion. The clash of secular freedom with Christian conservativism in '60s and '70s America may go some way toward explaining the rise of this structure. The enemies of independence in this structure are represented as savage monsters, or monstrous savages.

Now let's return to the film. Madness is a good instance of the travel-punish film. Two cheerleaders are on their way to a cheerleading competition. They stop at a gas station. There they meet and collect two men whose car broke down. One of the men sees the gas-station warning in the form of a creepy, masked man, but he ignores it. They are soon driven off the road and taken prisoner by brutish rednecks. Sadistic cat-and-mouse games ensue as the protagonists struggle to escape and the rednecks struggle to torture and kill their prisoners.

What makes Madness a good instance of the travel-punish film is the way it goes beyond the formula. Most travel-punish films are doggedly formulaic. There are usually around four victims and a killer or two. The killer(s) catch and torture the victims. One victim either gets away or all the victims die. That's all. Not so with Madness. There's a certain ineptitude to Madness that suggests the filmmakers, that is the three writer-directors (Sonny Laguna, David Liljeblad, Tommy Wiklund), weren't so much aware that they were transcending the formula. There are certainly some good creative decisions on display, but also a lot of creative and fortunate errors. In their amateur enthusiasm for the subject they stumble into transcendence. They manage more brutality and more realism than most other films of this kind. Living up to the title, there's just a certain madness to Madness that makes it all work. For instance, instead of sticking to the four protagonists, they throw in another victim who appears to be decomposing while alive. There was no need to include this character. His inclusion makes the narrative untidy. But there's a certain reality to that. It shows the inventiveness of the filmmakers and their eagerness to create more horror situations. Similarly, there's an extraneous villain who does little more than wander around in a bathrobe with a lantern. His inclusion is totally unnecessary. Yet his unexplained addition enriches the situation if only by its sheer mysteriousness. The inclusion of extraneous characters left me with the sense that we're not aware how 'big' this operation is. We're sure neither of how many killers nor of how many victims there are.

The camerawork is another instance of blessed ineptitude. That's not to say the compositions are bad; they aren't. However, the directors seemed to think shooting the whole film without a single tripod would be a good idea. And against all odds, it is a good idea. The camera is always wiggling at least a little as though we're seeing through someone's eyes. Add to this the filmmakers' knack for creative angles and the result is a strong paranoia. One senses the victims are always being watched no matter where they are. Their vulnerability is always thrust against us. They're babes in the woods.

Then there's the ineptitude of the characters. Despite being apparently prolific murderers, these rednecks are disorganized beyond anything I've seen in a film of this sort. They use weak duct tape to tie up some victims, fail to search their pockets for knives and matches, and leave weapons everywhere. There's one amusing scene that emphasizes this as a protagonist keeps exchanging his weapon for a better one. As silly as this seems, it allows for more creative scenes on the one hand and heightened realism on the other. Why must all backwoods murderers be extremely organized and efficient?

This realism extends beyond the ineptitude into brutality. The protagonists cry often. All the actors are Swedish and their struggles with English leave the acting occasionally stilted. But crying is universal. I had trouble deciding whether the crying is mean-spirited or humanizing. Ultimately, I found it to be humanizing, as I did start to sympathize with these characters. It could be seen either way, though, as it can be jarring to have characters suddenly humanized in a film of this sort.

There is another interesting feature of Madness. I couldn't help but notice that all the villains have eye problems. One wears thick glasses, another has a discoloured eye, and another has extremely sleepy eyes. They also spend their spare time watching rape films on VHS. They watch Cannibal Holocaust for sure. If I identified the dialogue correctly, they also watch Deliverance at some point. I won't go so far as to say there's a deliberate theme. There is nevertheless an interesting symbolic connection between watching violent films, damage to the eyes, and inflicting harm on others. That is the notion that the uncivilized eye sees and enacts what it sees, while the civilized eye can be assimilate violent imagery without making its owner violent.

So Madness may alienate some viewers due to its obvious flaws. There is, after all, a grammatical error in the first frame of the film. For those willing to see past the language barrier, however, Madness delivers a brutal, suspenseful horror experience. It has the sort of foolhardy inventiveness one can only get from amateurs. And I mean 'amateur' in the purest sense of the term: those who do it for the love of it.

Categories: 2010, horror, slasher Monday, April 12, 2010 | at 4:00 PM 1 comments

Uncharted (2009) - 1/4

Author: Jared RobertsThere are two basic schools of horror filmmaking. By no means are they mutually exclusive in practice, but it is fruitful to distinguish them in concept. One school recommends showing. The monster, the violence, and the gore is displayed to the audience. The other school recommends suggesting. The filmmaker hides the monster, the violence, and the gore, leaving the full scope of the horror to the individual imaginations of the audience. The Dead films of George Romero are clear examples of the showing school. Val Lewton's films are the apogee of the suggesting school.

There have been debates over which form is superior. The suggesting school is perceived as more artistic and intellectual, the showing school more exploitative. After making Val Lewton's greatest horror pictures (I Walked with a Zombie and Cat People), Jacques Tourneur made another classic, Night of the Demon. The film is infamous for showing the titular demon, a lupine puppet surrounded by smoke. The demon was the producer's decision. Tourneur protested vehemently against showing the demon. This is a neat microcosm of the debate. Tourneur believed showing the demon ruined the subtlety of the film, that the audience should be left in uncertainty and in the realm of possibilities conjured by the imagination. The producer thought of heightening tension. Both Tourneur and the producer are attempting to manipulate the audience, but to slightly different ends. Similarly, both the showing school and the suggesting school are trying to manipulate the audience, to horrify the audience. There are great films in both schools. Night of the Demon itself is still a masterpiece, employing both schools effectively. The demon bookends the film as a constant threat, while the middle of the film deploys the tactics of suggestion. The success of either approach depends on knowing how much to show and how much to suggest. Suggestion tends to be more unsettling and is ultimately less cathartic, leaving the audience disturbed after the film is over. If the audience is not given sufficient material to work with, however, the film is simply 'not delivering the goods.' It is more difficult to keep the attention of the audience with negation than with affirmation. The filmmaker must feed the audience suggestions. Showing tends to be more suspenseful and disturbing, but is ultimately cathartic. The audience usually leaves with the object of the disturbance resolved. If the audience is shown too much, there will be no tension but only a blur of concatenated make-up effects. This is an admittedly terse and monochromatic approach to the schools of horror filmmaking. I simplified the possibilities within each school for discussion's sake.

I mention this dichotomy because the inability to settle on either suggesting or showing is a major problem with Uncharted. Writer John Fuentes and director Frank Nunez make Uncharted a bit of both and fail on both counts. This indecision is related to another indecision, which I'll get to. Uncharted starts with a documentary crew crashing on an island in the Gulf of Mexico. Leading the crew is Laine (Elizabeth Cantore) a beautiful, female David Attenborough sort of adventuress and Greg (Demetrius Navarro) her cinematographer. Laine and Greg gradually realize they are on a very dangerous island as they are stalked and harassed by mysterious creatures. Except for late appearance of the plane's pilot, Uncharted is basically a two-person story. The rest of the crew is vanished before the film begins. What we see of them is in found footage. This is the other indecision. It seems Fuentes and Nunez couldn't decide whether to make a mockumentary horror film like The Blair Witch Project or not. They compromised by incorporating unnecessary found footage within the narrative.

I want to look at how these two indecisions are linked. The Blair Witch Project is one of the great suggestion horror films of modern times. One never sees the threat in Blair Witch, but only its effects. The mockumentary format means all we see is what is captured by the handheld camera of the documentarians. In the climactic night scene, the camera captures the panic as they flee into the woods haphazardly in order to escape a threat. All the audience needs to see is how threatened this people are. The threatening object is itself withheld. The mockumentary format gives an oblique, refracted perspective on the object of terror, a perspective filtered through the effect it produces. In its found footage moments, Uncharted struggles to accomplish what Blair Witch does. This even includes an homage to the famous nostrils scene. But the filmmakers don't seem to have grasped how Blair Witch earned its power. There is no build-up. The found footage interrupts the main action of the film. We see the documentary crew introduce themselves. They seem like nice people. One lady kindly flashes her large breasts to the camera. Unfortunately, these people are not a part of the story. Eventually Greg finds their camera and discovers their fates. Without any time alotted to build tension, they immediately wander offscreen, scream, and their bodies are found. The last victim drops the camera in such a way as to reveal furry hands pawing his torso. If the filmmakers wanted to show, they should have at least invested in showing well. Suggestion requires build-up. This is a part of the film that needed more and better showing.

Blair Witch also immerses the viewer in the filtered experience of the handheld camera. There is no external perspective. Most of Uncharted, however, is filmed regularly. The found footage tends to undermine the Laine-Greg section. The Laine-Greg section is the most successful. Initially the creatures appear as silhouettes against the tent in the night. They appear as black blurs placed behind and beside Laine without her realizing it. This technique gives the creatures a sense of being physical, but still nebulous, mysterious, like creatures from a Lovecraft tale. This is good. The material is given and the suggestion is earned. Then the discovery of the footage undoes much of what is earned. The furry paws contradicts the ratlike creatures the silhouettes made me imagine. The paws are more suggestive of a cheap ape costume. In this Laine-Greg section, where the attempts at suggestion are successful, it was important that the monsters and the gore be withheld. Unfortunately the filmmakers chose to do the showing in the Laine-Greg section. The film's final shot is a punchline reveal of what the creatures really are. I realized then that many of the film's mistakes derive from the desire to deliver this punchline. It's not a very good punchline.

It also amazes me how a film about serious people in a serious situation can still find ways of presenting the few female characters as spectacle. There are only two women. One is seen briefly in the found footage segments. She flashes her breasts at the camera a few times. She remarks how proud she is with her "new boobs," though they look real to me. Her boyfriend is also pleased with them. Laine, too, despite being a serious presenter of nature documentaries, finds time to get drunk and deliver a belly dance at the film's center. The belly dance is nice, but out of place. Unlike The Pit and the Pendulum (2009), there is no motif of body-appreciation. Unlike the virgin dance of the double chainsaws in Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers, there's no sense of inventive fun. Unlike the great erotic dance Debra Paget dances in Fritz Lang's The Tiger of Eschnapur, the belly dance serves no purpose for the audience, the characters, the story, or even for its own sake. The breasts and belly dance are presented in the most cynical way possible: because it's supposed to be there.

Uncharted is a film that does everything half-heartedly and cynically. There's no spirit of enjoyment. But perhaps that's uncharitable. Perhaps the hearts of the filmmakers were in the right place. Perhaps they copied the form but not the spirit of better horror films, not understanding that a good bellydance, a good gore scene, and terror are all things that must be earned.

Categories: 2009, horror, worst Friday, April 2, 2010 | at 8:21 PM 2 comments