Rosewood Lane is the latest film from Victor Salva. A vaguely supernatural thriller, it concerns the incessant harassment of a neighborhood by a teenaged paperboy. In particular, the paperboy becomes obsessed with Sonny Blake (Rose McGowan), a radio psychologist who has just moved into the house of her deceased father--who himself may have been murdered by the paperboy.

Victor Salva is always a complex filmmaker to approach, and not entirely for good reasons. Due to his unfortunate past, in which he sexually abused the boy star of his first film, Clownhouse, there is a tendency to look for biography in his work that may not be there--or, worse, to dismiss or express disgust with his work because of that past. Salva, however, is an undeniably skilled craftsman in the tradition of Spielberg, Coppola, and Hitchcock. Anyone ignorant of his past can enjoy his horrors and thrillers for the entertainment value alone. Nevertheless, Salva does have a tendency to personalize his films, a tendency often obscured by either unpleasant misreadings or pure enjoyment of the films. To do justice to Rosewood Lane, I will consider both the film's craftsmanship and Salva's personal expression.

Salva begins delivering the tension very early in the film. An elderly neighbor ominously warns Sonny against having anything to do with the paperboy. Salva compounds this advice with some eerie shots of the paperboy sitting stationary, on his bicycle, in the middle of the road, blocking the path of a moving truck. He's distant enough to be aloof from interaction, but the shots of him suggest he's watching and listening.

Soon, the paperboy is knocking at Sonny's door, and she's starting to notice objects in her house subtly rearranged. This begins an alternately suspenseful and infuriating cat-and-mouse game. The paperboy's seemingly supernatural speed and slipperiness, and his mystifying obsession with Sonny, give Salva the material to create considerable tension. The boy's smugness and abilities, however, can be infuriating. Had Salva not written Sonny as such a strong and intelligent character, this infuriating quality would have been tedious. As it is, however, our frustration is one we share with Sonny.

What ensues is really a power game to see who is going to dominate who. Sonny begins trying to reverse the cat-and-mouse roles by tracking down or chasing the paperboy. He manages to give her the slip each time with his apparently supernatural swiftness, even mocking her in some eerie setpieces. But she forces his hand to a final confrontation and a surprising conclusion.

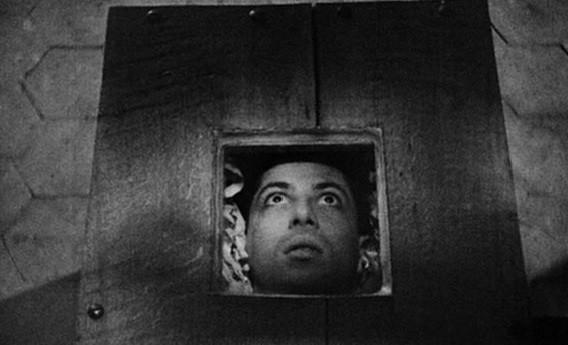

Salva enriches the material somewhat by Sonny a past haunted by childhood abuse. The features of the house Sonny used to avoid abuse--basement, heating vents--become the features the paperboy uses to hurt her. There is a somewhat psychoanalystic sense of the paperboy being Sonny's victimized past returning to victimize her, a sense probably not intended except to create more emotional tension, at which it succeeds. Mostly, however, it strengthens our conviction that Sonny is tough and unwilling to let herself be victimized.

The character of the paperboy is, as noted, very dislikable. And his ability to outsmart or at least outrun everyone can create tedium. Sonny's aggressive nature mitigates this somewhat, because what we're really wanting is someone like her to 'teach him a lesson.' However, I think this is an instant where Salva's personal interests have triumphed somewhat over his craftsmanship.

What we observe in Rosewood Lane is a handsome, underage boy trying to worm his way into an adult's home and life, a boy who deliberately takes pleasure in showing what power he can exercise over adults. When he sits in front of the moving truck, for instance, or when he moves objects in Sonny's home; just being in her home or even the mere act of listening to her conversations, are ways he exercises power. (Listening is a relatively common technique children use on adults, especially foster children who need to feel in control of their situation more than most children.)

Knowing Salva's past as a convicted child molestor, it is difficult not to make something of this. But, in order not to be trite or glib, we have to be careful not to read in our own prejudices. The superficial reading would be that the film's dynamics represent a sort of allegory for Salva's own obsession. He struggles to lead a normal, respectable, and, due to his work, mildly public life, all the while he is victimized by this boy. The boy represents his own obsession with boys, and the boy's incredible sneaking powers shows how hard it is for Salva, how anywhere he turns the obsession may have slipped in unnoticed, much as how Jeepers Creepers II features a group of attractive, teenaged boys without shirts.

While that would be a fairly accurate picture of how such sexual addictions work, and while that may even partially describe what Salva is expressing, I don't think it exhausts it. I think Salva's mind is more complex and his vision more ambiguous.

The primary characteristic of the paperboy is his defiance, his need to express his own indomitability and his power over others. I don't think it's just the nature of addiction being allegorized in the narrative's action. I think, for the addict, the object of addiction is dominating and defiant. It exerts a power over the addict that he or she does not want it to do. This is true especially in one's fantasy life. And to pursue one's fantasies in the real world, as Sonny's pursuit of the paperboy, is doomed to failure.

I don't want to suggest Salva is cast into turmoil every time he sees a boy, but I do think the narrative presents a case of victimization by a boy that is akin to what someone like Salva may sometimes feel. That Salva's film releases have routinely been protested by his victim, Nathan Forrest Winters, adds another element to the idea of boy as dominant and defiant.

Reading more elements of the film into this sort of analysis would be possible. But I don't see the value in taking it any farther. Salva's films always seem torn between entertaining and expressing, and he always prefers to err on the side of entertainment. As he's quite good at creating suspenseful setpieces and his films have never yet failed to entertain me, I don't see a problem with that. Rosewood Lane is a suspenseful, fun film thanks to Salva's skill for thrills and McGowan's tough-but-vulnerable performance.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

Rosewood Lane (2012) - 2.5/4

Author: Jared Roberts

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)