(I wrote the following essay(s) in October 2010, but for one reason or another it was never completed to my satisfaction and thus never published. Reading it over, I think it is publishable; however, as my memory of the films, not to mention my own train of thought at the time, is too diminished to complete it, it remains in incomplete work. - JR, Sept. 28, 2011)

Un jeu d'enfants (2001) - 2.5/4

Promenon-nous dans les bois (2000) - 2.5/4

The horror film, for its ability to fly under the radar, to directly target the emotions, and to push against or beyond the limits, has often been considered as both the most subversive and, paradoxically, the most conservative genre. More paradoxical still is how subversion and conservation are achieved in the same stroke according to such critics as Robin Wood and Bruce Kawin: the monstrous and subversive force is allowed to roam free only to be destroyed at the end, leaving the audience to go home with their catharsis. Of course, horror films have never been so simple. The films of James Whale are intentionally more subversive than conservative. In Bride of Frankenstein, for instance, the Bride rejects the male for whom she was made, her expression of free will being the film's very climax. The slashers of the '80s, on the other hand, are considered by many feminist critics to be the height of ideologically conservative films.

Some filmmakers, moreover, strive to be subversive and unwittingly create a conservative film; sometimes the very converse happens. I have no knowledge of the filmmakers' intentions in Un jeu d'enfants and Promenon-nous dans les bois; but whatever their intentions, one has turned out a decided assault upon the traditional Western family form and the other a fierce protector of its sanctity.

(These reviews contain some spoilers.)

The Conservative: Promenons-nous dans les bois

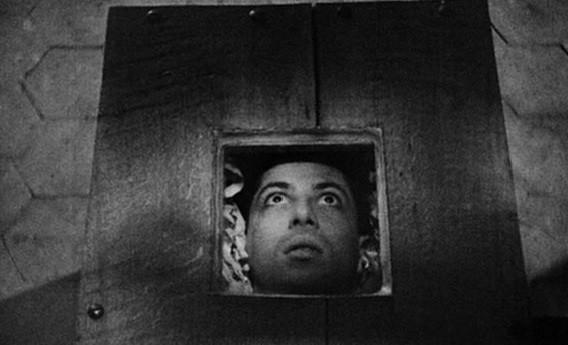

Promenons-nous concerns a group of young actors who are invited to the mid-forest chateau of a rich eccentric in order to put on a panto performance of Little Red Riding Hood. The fun-loving, attractive youths find him an uptight, wheelchair bound homosexual living alone with his nearly-catatonic grandson and gamekeeper. After the performance of the play, the sun sets and the group is targeted by murderer in a wolf costume.

What the film emphasises, in the midst of the unremarkable slasher material that ensues, is two very different but equally non-productive coupling forms. The company of actors is promiscuous, their relationships ephemeral. For lack of a better term, they're 'fornicators,' without a family form. The group, in fact, contains only a single heterosexual couple. One male is single and potentially bisexual, one female lesbian, another bisexual. It is a voluntarily non-productive group that directs its actions to pleasuring itself. Taking the group as a unit, it is essentially masturbatory.

On the other hand, the situation into which the group enters is a family consisting entirely of men: the grandfather and the little boy. The gamekeeper has a sometimes-submissive and sometimes-dominant role in relationship to the grandfather that at times flickers wife-like. So this unit is similarly non-productive, albeit for different reasons. If the group of youths are non-productive from an excess of Eros, the chateau denizens have a deficiency of Eros and instead embody Thanatos. The grandfather, indeed, compulsively repeats Little Red Riding Hood tropes from his own youth, but curiously treats the wolf as the protagonist, Hood as an invader. (The repetition of the past is, in psychoanalytic theory, a function of the death-drive, Thanatos.) The gamekeeper has a taxidermy hobby and is a rapist. The chateau is thus committed to merely subsisting, consuming but producing nothing.

The climactic reveal of information is, significantly, pertaining to the family situation of the chateau. The grandfather's daughter, while pregnant with the boy, tried to escape the family and, mid-flight, was caught by the grandfather and the gamekeeper; they cut the child from her womb and left her to die. So not only is the situation deprived of female presence, it is openly hostile to the necessary female presence in sexual reproduction, to the family situation that is ordered around sexual reproduction. It is as though she were killed for her productivity.

I mentioned James Whale above. The film can be compared, in subtext, to Whale's far superior film The Old Dark House. In The Old Dark House, a group of youths (or what passed for youths in the '30s) enter a non-productive family of old eccentrics, the women masculine and the men feminine. The only vital presence in the household is Boris Karloff's butler character, whose energies are devoted to one of the effeminate men. Whale went so far as to cast a woman as the family patriarch.

In Whale's film, normality is represented by the young crowd who enter the house seeking shelter and who ultimately leave the house in flames, normality restored. Whale's sympathies, however, seemed to lie in the titular Old Dark House, not with the sentimental young couples. Promenons-nous doesn't divide its sympathies from its results, going a step further than Whale in both restoring normality and approving. In Promenons both the family and the youths are abnormal; their collision results in both groups being destroyed and the remnants assembling into a makeshift family. Of the chateau only the boy survives, of the group one male and one female: the makings of a nuclear family. The boy, nearly-catatonic throughout the film, for the first time smiles as he drives home with the surrogate mom and dad; and on that the film ends, with happiness gained by destroying promiscuous heterosexuality and essentially non-productive homosexuality. In short, finding happiness is co-extensive with maintaining the ideological order as it pertains to sexuality and family forms.

The Subversive: Un jeu d'enfants

Un jeu d'enfants begins with an ideologically perfect family: a work-at-home mom, an office-worker dad, a son and a daughter, both around seven years of age. With their financial security they take an enormous apartment which may turn out to be their undoing. An elderly brother and sister pair arrive at the door one day requesting a tour of the apartment in which they grew up. The mother obliges the decidedly creepy couple, briefly loses track of them, and escorts them out without incident. However, once the couple leaves, strange things begin happening and the mother is convinced the old couple had something to do with it.

Jeu is not exactly a haunted house film, but the concept of place is important all the same; nor is it a possession film, but the loss of identity is also important. Somehow merely inhabiting this apartment, where an earlier family ended in tragedy, begins to tear at the fabric of the well-ordered family. The essence of the patriarch is to earn the money, so naturally the father, when he begins attacking an imaginary offender at work, loses his job. The essence of the wife is her fertility and fidelity, so naturally the mother begins having random sexual encounters with servicemen. The children, however, are the most affected, seemingly taking on the characteristics of the elderly pair and thus becoming independent beyond their years.

The ways in which the apartment effects these changes in its occupants remains mysterious. In fact, Jeu is so committed to ambiguity there's not much one can be certain of. The elderly pair seem not to exist outside of the wife's mind; the adulterous liaisons the wife engages in may not have occurred at all, given the bizarre way the servicemen are represented. The repairman, for instance, screws her as methodically as he works on the washer, calmly walks away when she tells him he's done. One wonders if there isn't a psychedelic fungus in the apartment. But the film gives no basis for this in the narrative, so we're left with a family disintegrating in their new apartment for no other reason than that a previous tragedy occurred there and some occult forces have determined the next must follow suit.

Ultimately Jeu is a nightmare of the middle-to-upper class nuclear family, the tensions of which arise from individuals resisting the roles the structure thrusts them into. In Jeu, the home, the central place of family life, perverts each individual into the opposite of the role they are expected to occupy: the patriarch becomes impotent and dependent, the mother a whore, and the children begin to dominate the family. When the fate of the family situation is decided by the children, it is inevitable that it is consumed.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

The Family: Un jeu d'enfants (2001) and Promenons-nous dans les bois (2000)

Author: Jared Roberts

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)