Much to the delight of old Romantics like myself, there have been two strong anti-political cinematic statements in 2009, both by well-established filmmakers. These are Inglourious Basterds (Tarantino) and The Limits of Control (Jarmusch). Tarantino asserts the power of entertainment over politics and his film is so entertaining it triumphs over some of the most hardened hearts, save for Armond White and a few die-hard politicals. Jarmusch, on the other hand, asserts the power of art over the pragmatics of life, of which politics is of course a subset. Jarmusch, however, does not make his film itself a great work of art, and for this reason his message, to which I am entirely sympathetic, fails.

I have oversimplified Jarmusch's mission with The Limits of Control. To do him justice, we shall have to gird our loins and wax philosophical. There is a French philosopher-sociologist by the name of Bruno Latour. Latour had the idea of studying science laboratories the way anthropologists would study a tribal village and see what could be learned by putting scientific practice itself under the sociological microscope. He came to the conclusion, based on the data he collected, that science is more or less made up. For instance, there was no proof of the electron: it was an idea that was postulated to explain some observed phenomena and the scientific community agreed it exists. In this sense, science creates its own reality, according to Latour. Since science has something of a monopoly on truth in the west, this reality is one to which the majority subscribes. But that's not what's important. What's important is that science creates a reality. By the same token, each of the arts can be said to create an individual reality by means of its perception: music, literature, cinema. Is the reality of cinema the same as the reality of literature?

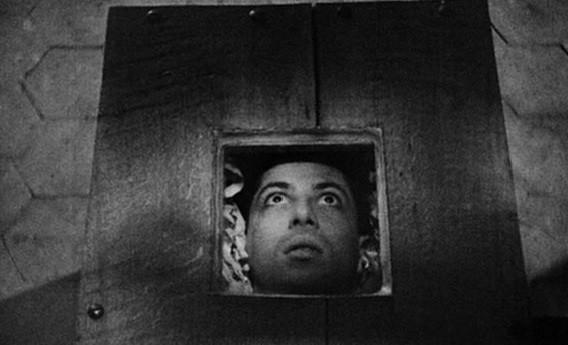

Jarmusch infuses this Gallic theorizing with the Romanticism I noted. A nameless man (Isaach De Bankole), who is either a secret agent or a mobster, travels Europe meeting one agent after another. Each agent delivers the same code phrase, then a monologue on philosophy, or science (chemistry, linguistics), or an art (music, painting, cinema), leaves a matchbox containing information, and departs. (This structure covering each of the arts, incidentally, is not post-modernism but modernism: it was previously employed by Melville in Moby Dick and James Joyce in Ulysses.) One character (Bill Murray), the only 'practical' character in the film, decries the uselessness of the arts and sciences for real life. For this character, what is not useful for practical reality is mere pollution of the mind. In this time when most critics, particularly academic critics, are only interested in a film of it displays politically relevant content, Jarmusch's point is a very pleasant one. It should be clear just by my description that the film is allegorical. Each of the monologues on an art is indeed useless to the nameless agent, whose sole purpose is collecting notes and diamonds, it seems. Tout ce qui est utile est laid, as Theophile Gautier put it. All that is useful is ugly. Each area of human inquiry is a reality of ideas worthwhile for its own sake. This is the position Jarmusch appears to be affirming.

I say 'appears to be' because it is entirely possible I missed some nuance; some ironic subtlety may have evaded my grasp. For instance, the emotionless protagonist never clearly enjoys any of the arts; he never gives any sense of enjoyment at all. On the other hand, Jarmusch gives no indication of sympathizing with this character. Rather, the characters he presents most sympathetically are the various monologue-reciting agents the man encounters, particularly Swinton's character. If I am correct, then the problem with Jarmusch's film is just that it was so very easy for me to figure out: it's too sincere. Art, and cinema is an art, arrives at truth by telling a series of lies. A series of truths that lead to a concluding truth is an argument and an argument is the substance of an essay. Jarmusch is creating an essay in cinema, but an essay that is made up of lies, that is, rhetorical tropes (allegory, metaphor, indeed the whole narrative is a rhetorical technique). While some might complain of Jarmusch being too cerebral, ironically my complaint is that he insults my intelligence. If Jarmusch wanted to write an essay on how French sociology, all influenced by Foucault, points to a new Romanticism, he should have taken his audience seriously by writing an essay with acceptable premises and a logical conclusion. This is taking the intelligence of the audience seriously. Poetry and rhetoric to establish an intellectual point is manipulation. He is trying to trick the audience into seeing the position he's taken. It's an assertion with persuasion rather than an argument. What might have been a good essay, if old news (Latour wrote his best work in the '80s), has become bad art.

Despite my displeasure with the overwhelming sincerity of The Limits of Control, I did enjoy the picture. The character who delivers a monologue on cinema (Tilda Swinton) praises particularly the non-narrative aspects of cinema. She explains that she likes moments in movies when nobody is speaking or performing significant action. I agree with her; I also enjoy quiet, inactive moments in cinema. Like her, who I believe to be a mouthpiece for Jarmusch, I appreciate the sociological and historical data to be found in cinema. As such, The Limits of Control is a delight. It is made up almost exclusively of such moments. Even the film's action has a certain passivity. A strangling occurs as matter-of-factly as a sip of coffee--for both the strangler and the victim, curiously enough.

As is often the case with films that boast an impressive cast, cries of "Over-indulgence!" can be heard from the reviewers. Art is supposed to be indulgent; there's no such thing as 'over-indulgence' in the arts. If anything, Jarmusch didn't indulge himself enough. He brings in his mind, but what about his deeper, inarticulable sentiments? The film's reception suffered the Ishtar-effect anyway. The Limits of Control is not just a "star-studded" film, though it looks that way in a list form. But a list is not the film. Watching the film, the cast does not get in the way. Rather, what one sees is a series of exquisite casting choices. Though they play small roles, Swinton, John Hurt, Bill Murray are maximally effective.

I wish very much I could say more about the visual style of the film, but I feel woefully inadequate to the task. It is a beautiful film. The cinematography and techniques are fascinating, particularly the way some shots are inverse copies of others. But as more philosophy student than film student, it takes me considerably more effort to do a visual analysis and I am clearly of the opinion that The Limits of Control is not worthy of that effort. Perhaps a clue in the visuals would reveal I have been unfair to the philosophical content of the film, but I couldn't see such a clue and, that being so, I don't see such a sincere film rewarding too close an analysis. There are better films out there making similar points to The Limits of Control and not insulting viewer intelligence in the process. I have in mind, of course, Inglourious Basterds. Good entertainment is always preferable to bad art.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

The Limits of Control (2009) - 2.5/4

Author: Jared Roberts

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

Hi, Im from Greece and I am trying hard to do a translation. I stumbled on the word Boyg wich I suppose is a name or a place, but I cannot find any information about it. "..no such Boyg appeared on the hillside" Please, tell me if you have any idea what does he mean? I guess is a metaphor but I dont know what kind. Thank you for the nice blog also. Greetings

The name 'Boyg' comes from the Henrik Ibsen play, Peer Gynt. The Boyg is a monster of sorts and every attempt to attack it or get past it is futile. In the context you refer to it, it probably refers to an activity that is futile. It's rather an odd phrase.

Post a Comment