Have you ever heard of Pete Walker? Walker is a British director of exploitation pictures. He was the first to bring sexploitation films to the UK. As the public lost interest in the output of Hammer Studios, Pete Walker filled the gap by writing and directing violent, bloody horror films. They also happen to be very good films. One of those films is House of Whipcord, made in 1974. It's a classic exploitation film, far more intelligent than the women-in-prison material would suggest. Penance is an unofficial remake of House of Whipcord. Walker is given no credit. But the story and characters are too similar to House of Whipcord to dismiss the similarity as a coincidence. Official or not, horror remakes generally purpose to make the original material scarier and more horrifying. Penance does just that. Walker's film is more intelligent than Penance, but it's not scary nor is it as lurid as one would expect. Penance is a lurid, disturbing film with some scary moments.

There are of course some creative changes from Whipcord. I think going through some of them will be illuminating. In Whipcord, a young woman who consented to a single nude photograph for an art photographer is seduced and brought to an abandoned clinic. There a judge, his female warden, and their two female assistants have established a court and penal system based not on legality but morality. They want to rehabilitate immoral women. In Penance, writer-director Jack Kennedy changes the target from just generally 'immoral' women to strippers. Amelia, an employee at the battered women's shelter trying to raise money for her daughter's medical bills takes a single high-paying stripping job her sister secured. The job turns out to be a trap set by a doctor/general and his two female assistants. In his abandoned clinic he tries to rehabilitate by violent means the women he deems impure.

Walker's focus is on the moral elite who believe they can legislate and enforce their personal morality on those who don't share their values. Whipcord emphasizes the generational gap. All of Whipcord's prisoners are attractive young women and the administrators are all elderly. The moral laxity perceived in these young women is pretty tame by today's standards, but shocking to these elderly prudes. But Kennedy, by focusing on strippers, is calling attention to sexual objectification. During a practice stripping gig, Amelia (Marieh Delfino) is almost raped. Her sister is later given a black eye. Kennedy calls attention to this peculiar phenomenon in which strippers are treated as non-persons. Both those who are excited by strippers and those who are indignant toward strippers share this point of convergance. When someone is taken to be a sexual object, one is permitted to do to her what one pleases. Sexual objectification is shown to have dangers far beyond mere degradation. The removal of one's status as a person worthy of respect means no moral duty is owed that person. That is Immanuel Kant's contention. Sartre also explored this issue. In Being and Nothingness, he argues that there are many possible attitudes with which we try to preserve our subjectivity from the objectifying gaze of other people. Sexual desire is one of those. But the failure to objectify the other through sexual desire leads into sadism and ultimately desiring someone's death. The process Sartre describes is exactly the process at work in Penance. As women who are taken to be objects of sexual desire prove to be real people and thus resistant to objectification the attitude taken toward them is sadism. The captors whip these women and stun them with electricity. As sadism, too, fails to reduce them to objects or non-persons, they must be killed.

Walker's House of Whipcord, consequently, takes particular interest in how the prison is run, from the point of view of both administrators and prisoners. The plight of the heroine and a few other girls gives the audience a sympathetic center with which to observe. We follow their treatment, their escape attempts, their beatings and sometimes deaths. Penance begins similarly, but quickly abandons exposition of the prison's processes in favour of Amelia's ingenuity, abuse, and escape attempts. The film is a series of suspenseful, lurid, and downright cringe-inducing moments. Whipcord had surprisingly little nudity. Even the whippings were eroticized more by the perverse characters than by Walker's camera. Kennedy has no scruples. When Amelia is whipped, she's strapped naked to a spring bedframe so we see her large breasts pressed up against the latticework. There are, moreover, scenes of genital mutilation. Kennedy is gentle enough to leave the actual mutilation offscreen. Yet they are certainly uncomfortable moments. If anything leaving the mutilation offscreen made the scenes more effective. Genital mutilation on women remains a widespread activity in the world. The focus on the abuse of women and the resentment of female sexual desire in Penance elevates what could have been mean-spirited torture scenes to some degree of seriousness. It is there for a purpose; Kennedy earns those scenes, however unpleasant they may be. A little of the maturity Walker brought to House of Whipcord has carried over to Penance.

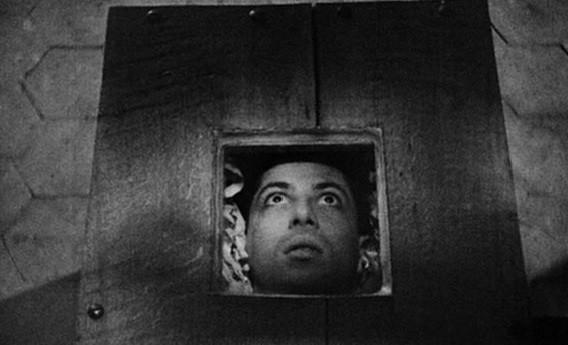

The major departure from House of Whipcord is the format. Penance, against all odds for what is essentially a women-in-prison film, is also a mockumentary horror. The whole film is supposed to be footage recorded on a miniDV camcorder. This restricts the film in ways Whipcord isn't. Walker was free to show any action he wished from any angle and with any camera movements. Kennedy is bound to a few camcorders. To make this work the administrators of the prison must be comfortable allowing Amelia to film everything. This is odd. They even have their own camcorder that they use on themselves. To Kennedy's credit, he perceives the peculiarity of the captors allowing themselves to be filmed and compensates. He makes the doctor a narcissist, frequently looking in an ornate hand mirror. Where credulity is strained the most is the scenes of suspense. To peer around a corner exposes a part of one's head. To peer around a corner with a camcorder exposes hand, head, and camera. Whenever Amelia escapes and spies on her captors, even from a mere three feet away, they are somehow oblivious to her presence. They are the least observant people in cinematic history.

The restriction to camcorder footage limits the nuance available to Kennedy as well. The captors in Penance are not permitted to be the complex individuals we find in House of Whipcord. The only one we get to know is the doctor (Graham McTavish). That's too bad. I was fascinated by Alice Amter's performance as the sadistic and sexually repressed assistant with the stun gun. But the doctor keeps the cameras on himself. He is a grotesque. His motivation is pure religious mania, as the film's title indicates. He believes he is making the path to heaven easier for the women he tortures and murders. He's consistant enough to take penances himself. Yet he does have a few subtle contradictions. He drinks wine while taking an ice bath, for instance. In Whipcord, Walker gave us real people with monstrous minds: Barbara Markham's warden is fury of sexual repression; the judge is a confused old man who believes the girls are being released cured of their immorality; the aides are clearly closeted lesbians and sadists. In Penance, we're given one-sided monsters. One of them, "The Man" (an excellent cameo by Michael Rooker), is particularly frightening.

By limiting his characters, Kennedy unwittingly undermines his social commentary and expresses the very attitude he's condemning. Just like his grotesque characters, Kennedy too is contemptuous of his sexually liberal strippers. As the film progresses through the third and fourth acts, the strippers are never seen. It is implied that they've all been killed offscreen. Only Amelia, the non-stripper, goes on fighting. He could have made Amelia a stripper. But he chose to make her a non-stripper. She's a victim because she's a 'good girl.' The implication is that the other women had it coming. He offers the abuse of the women to the audience for enjoyment. Their breasts are pressed up against latticework. When they fall from electric shocks, we see the perineal panties scrunched between their thighs. While Amelia shows sympathy for the abused strippers, Kennedy is content to forget them. I doubt this was his conscious attitude. However, in losing the nuance of Walker's film and simply presenting the captors as bad prudes and Amelia as a good girl in the wrong place at the wrong time he opens himself to the same charge he levels against his captors. At the end of the film we've seen our own perverse desires to punish women who earn a living exploiting male sexual drive and seen those perverse desires themselves punished. It's a cathartic repression that leaves us secure in our attitudes toward sexually objectified women and in our bad faith.

I can't deny my contempt for Kennedy's dishonesty. Some credit should have been given to Pete Walker. I also can't deny that Penance is an effective update of House of Whipcord. It goes places Walker couldn't or wouldn't go and does so legitimately. There are no stretches of logic, only stretches of taste. It manages to maintain a level of maturity in the midst of the torture and terror. And it uses the subject matter to explore different issues. That's much of what a successful update ought to do. A successful update should also give credit where credit is due.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

Penance (2009) - 2.5/4

Author: Jared Roberts

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment