There is considerable presumption in titling a film, even a film directed by Dario Argento, Giallo. The giallo film is, of course, a highly-influential subgenre of horror-thriller that flourished in the '70s thanks primarily to Argento, as well as Lucio Fulci, Sergio Martino, and, the maestro, Mario Bava. For Argento, after making giallo films for nearly four decades, to make a film called Giallo is tantamount to promising us a total summary of his career thus far, a summa of the whole subgenre, from The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963) to Do You Like Hitchcock? (2005). Giallo does not keep that promise.

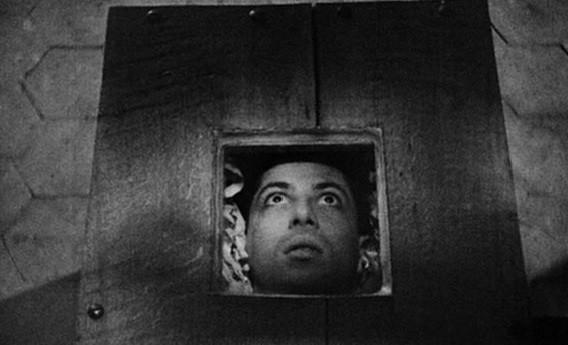

Giallo concerns a killer, known as "Giallo," who kills for abstract sexual gratification. A hideous, troll-like man, he targets women whom he could never bed and traps them in his taxi cab. As a proxy for real sex he tortures and kills the women. One of the women is a model who happens to be using her cell phone when kidnapped. Her sister Linda (Emmanuelle Seigner) thus has a lead and works closely with the maverick inspector Enzo (Adrien Brody), whose mother was murdered before his eyes as a child. The film is a straight-forward police procedural of trying to find the killer and save the girl.

Giallo, alas, is not written by experts, but by casual fans whose previous works have all been CGI monster movies for the Syfy channel. Had the film been scripted by Argento himself, it may have attained some sublimity. Sean Keller and Jim Agnew, however, only understand the superficial conventions of the giallo film: sadism to women, an opera (referencing Opera (1987)), a taxi (referencing Suspiria (1977)), and the man-woman detective team (referencing Profondo Rosso (1975), amongst others). Imagine a Hitchcock tribute film consisting primarily in close-ups of keys. This is indeed a link to Hitchcock, but a very superficial one. Similarly, Keller's and Agnew's grasp of the essence of the giallo film is superficial.

The essence of a giallo film, more than anything else, is grounded in amateur detective work. From The Girl Who Knew Too Much onward, the police are scarcely a presence in solving the crime in a giallo. The police proceed by a rational methodology, much like the viewer weened on Sherlock Holmes stories, that proves ineffectual. The protagonists are nearly always individuals who are by chance privy to a sliver of information they can't fathom. (That, incidentally, is an important trope left out of the Agnew-Keller screenplay.) Like the symbolism of a novel, one must reach the end before the significance becomes clear. The detective process is thus not one of deduction, as in Sherlock Holmes stories, but one of hermeneutics, interpreting material as one interprets a poem; the amateur detective uses lateral thinking, following instinct, personal inclination, and sometimes ideas that are entirely inexplicable. The masterpiece of hermeneutic detective work is Argento's own Profondo Rosso. In that film, Marcus Daly first remembers a lullaby he hears during an attempt on his life; he is then informed that the lullaby was written of in a book of local legends; he then tracks the book down and finds a picture of a house inside; he then inquires from a florist about the plants in the photo so he can locate the house, even though he has no idea if the house is significant. After finding the house, we realize he's actually stumbled into the site of a murder we witnessed in the film's prologue and on it goes until he does indeed stumble upon the killer. Marcus's detective work is not a process of deduction. He couldn't logically draw any links between the moves he makes. Yet, he finds the killer while the detectives eat sandwiches and shrug their shoulders. That is the essence of the giallo.

Starting with The Card Player (2004), Argento started to evade this giallo convention into flat-out police procedural. I would go so far as to argue The Card Player is not a giallo at all, but that's a discussion for another essay. Giallo continues the style of The Card Player, following a detective, Enzo. Enzo claims to not play by the book, yet his investigative procedures are basically logical, tracking evidence and waiting for lab results. The only unorthodox feature in his method is how he treats the criminals. Basically, he kills them. I'll come back to that later. Enzo does get an assistant in Linda, the sister of the killer's latest victim. While she aids in the investigation, her discoveries too are purely logical. She deduces from the last words of a victim, "yellow," that the killer probably has a liver disease. That makes too much sense for a giallo. So one of the most fundamental aspects of the giallo tradition is absent. The investigation in Giallo is not a hermeneutic effort, but a deductive one.

Complementing the amateur detective work is the audience involvement in the investigative work. Ordinarily the killer kills for a motive of sexual perversion so convoluted as to be virtually un-guessable, such as the gender confusion in Four Flies on Grey Velvet. That the amateur detective manages to figure out who the killer is comes as something of a shock. And yet, when the motive is itself illogical, how could anything but an illogical investigation uncover it? The method of investigation ideally suits the object of investigation; the form fits the content. One might even go so far as to say the elegant murder set pieces that occupy a traditional giallo (also absent from Giallo) are works of art that demand not investigation but interpretation to solve. The consequence, at any rate, is that we never know more than the protagonist. In fact, as the protagonist's leaps of "logic" can be difficult to follow, we often know less. Discovering who the killer is and why the killer has been killing all along is one of the singular pleasures of the giallo tradition, sometimes outstripping the coda of Psycho (1960) in sheer over-explanation.

This, too, is absent in Giallo. We're shown the killer around the middle of the film, before Enzo and Linda find him; and when they discover who he is even by name, we can only shrug. He's just a guy. There are no red herrings--a fundamental feature of giallo films, especially Sergio Martino gialli--leading us to think it may be one of several familiar characters. Even The Card Player featured this trope. Giallo does not. The killer is a man named Flavio Volpe ("Blond Fox"). This is not a spoiler, as you will never meet him except as the killer. And his motive is uncharacteristically simple: He's ugly and gets his sexual gratification from torturing girls. The sexual perversion trope is indeed present, but highly simplified in comparison to Argento's earlier pictures, such as the baroque Trauma (1993).

All of this discussion is to say that Giallo is not a summa giallica; it may not even be a giallo. This wouldn't be significant were the film not obviously representing itself as the ultimate giallo, or, what the screenwriters themselves called a "kitchen sink giallo," were the film not superficially attempting to be a summary of giallo tropes. That does not, of course, mean the film is necessarily a failure. Even if it isn't a giallo, it can still be a good crime-thriller. But it isn't that either.

Enzo is a frankly charmless detective, very far removed from David Hemming's Marcus Daly in Profondo Rosso. Brody, himself a very charming screen presence, struggles to make Enzo appealing with minimal success. The notoriously wooden Emmanuelle Seigner, moreover, is fiercely arborial thanks to her vapid character. This leaves the twisted Giallo to amuse us and he actually does, with broken English lines like, "No move or you blind" and the general glee with which he sets about torture. He's seen reading a pornographic comic at one point. A knowledgable friend informs me the comic is a Final Fantasy 7 comic depicting one of the main characters sexually engaged with a dog. So he masturbates to cartoon bestiality as well as pictures of the tortured women. What a guy. He's a grotesque portrait of slacker/doper culture, inhaling aerosol and masturbating all day. Unfortunately, we spend much more time with Linda and Enzo than we do with Giallo.

The film's strongest point is in drawing a link between Enzo and Giallo. Both characters have suffered trauma and both characters have turned to violence in response. Enzo, as mentioned, witnessed his mother's murder. We see this in a beautiful flashback. Giallo also gets a frankly implausible flashback to his in utero existence, where his heroine-abusing mother ruined his life from the start. Giallo mutilates women, perhaps as revenge on his mother and perhaps out of sheer resentment. Enzo plays maverick detective. Once he finds a killer, he kills him. He never explicitly says so, but the film strongly implies this is what he does and that the chief employs him for cases that require this maverick behaviour. He's a police assassin and his current target is Giallo. This creates the narrative's sole moment of moral complexity: If Enzo kills Giallo, they may never find the girls he's kidnapped. Satisfying his bloodlust would therefore be as selfish an act as Giallo's self-gratification.

The film's weakest point is in the near absence of female content. One of the most curious stylistic choices of the film, and one that's repeated too often to be unintentional, is having helpless women yelling out repetitive insults at men from the background. Men dominate and women are helpless and irritating voices of outrage, chastising them from the background or from out of frame. Rather than have any emotional effect, these moments are annoying. One of the victims yells at the killer, as he goes about his business, that he's ugly and he's sick. She yells this a good two dozen times, mostly from out of frame. A later rhyming scene has Linda yelling at Enzo from the background for far too long. I can see what Argento and the writers were trying to achieve. For one, they again link Enzo and Giallo. They also represent women as a damaging influence from behind--the background and offscreen serving as a metaphor for the past, haunting both Enzo and Giallo. But the effect is just to make the only women in the film with any significant screentime extremely annoying. They are shrill voices, banshees, assaulting from out of frame or out of focus. An interesting but ultimately flawed stylistic choice that poisons the few glimmers of femininity in the film.

Despite the multitude of flaws, Argento's visual style pulls one along so that the film never quite becomes boring. Occasionally it insults, occasionally annoys, but never bores. Nevertheless, one hopes Argento either return to writing his own screenplays, or find much better screenwriters in the future. Argento's style just couldn't save the film from a hopeless and misguided screenplay, or, to be fair with the blame, his own peculiar artistic choices.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

Giallo (2009) - 2/4

Author: Jared Roberts

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comments:

About damn time!

Post a Comment