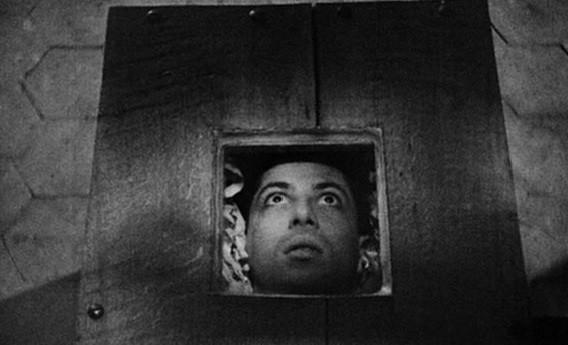

Brad McCullum (Michael Shannon) has murdered his mother (Grace Zabriskie) and barricaded himself inside her house with two hostages. The film's tagline tells us, "The Mystery Isn't Who. But Why." My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? "Inspired by a true story" of a man who killed his mother with a sword after over-identifying with a character he was playing in The Eumenides, Orestes, who also kills his mother. Herzog doesn't accept such a simple explanation as "over-identifying." The whole film is constructed around answering the 'Why?'. However, contrary to the tagline, understanding the 'Who?' is the key to understanding the 'Why?'. Most of the film is comprised of a series of flashbacks triggered by Detective Hank Havenhurst's (Willem Defoe) questioning of Brad's fiancee, Ingrid (Chloe Sevigny), the play director, Lee Meyers (Udo Kier) and the neighbours, Mrs. and Miss Roberts. The flashbacks reveal to us the strange life and behaviour of Brad in the time leading up to the murder. We learn there are two major events that precipated Brad's crime: he visited Peru for a rafting trip and came back hearing the voice of God; and he starred in The Eumenides. In other words, no explanation at all.

There are two very important shots that reveal more about Brad than Ingrid and Meyers do, each in one of the two flashbacks to Peru. In the first, we see Brad standing before the river, splitting the frame in half: one half is the green land, the other half is the white rapids. Gazing toward the river, Brad yells at his meditating companion that the river is reality. So in this shot, Brad is still facing reality. In the second flashback to Peru, the group has moved down river some. Now Brad is sitting on the rocks, facing the opposite direction of the river. One companion tells him he's behaving strangely and he says, "I'm just looking at the river," which is patently false. Brad is now no longer facing reality. Ingrid and Mrs. Roberts tell us Brad changed after his trip to Peru, but they can't explain why. Ingrid thinks it's the death of Brad's travelling companions, but the flashback clearly shows Brad's madness setting in prior to their deaths. Temporally, we can't see what happened in between the flashbacks to suddenly trigger his madness.

However, Herzog gives us one flashback--which occurs suddenly, without trigger, and is not told by or to anyone--between the two Peru flashbacks. It's a quiet shot of Brad's mother poking a piano key, then walking over (the camera follows her) to Brad, who sits at a drum set. She complains that Brad never plays his piano or his drums. We can also see a guitar at the bottom of the frame when she's at the piano. Brad tells her that she's the one who "tried to persuade" him to want the drums. We have no idea when exactly this moment occurred in Brad's life, but Herzog plants it between the two Peru flashbacks for a reason: in between facing reality and not facing reality is Brad's lack of direction in life, his inability to commit himself seriously to any vocation. As the film goes on we learn he used to play basketball, was into New Age thought (along with his fellow rafters), briefly got the notion to go whitewater rafting, decides to become a Muslim and ditches out of the rafting, decides to become a stage actor, and even, as he's being taken away by the cops, announces "I have taken a new vocation as a righteous merchant." He's a dilettante: he wants to do everything but will commit to nothing. He wants to continually remake himself according to each new fantasy and, in doing so, withdraws further from reality until fantasy and spontaneous self-reinvention takes over.

Brad is a model of this generation's malaise. We live in a wonderful time when so many options and opportunities are open to everyone. I decide I want to be a film critic, so I start this website. If I want to be a filmmaker, I can easily pick up a camera and put out a casting notice. So many options are open to us, as they are to Brad, that in this generation we have difficulty choosing just one or at least having the discipline to stick with one for a reasonable length of time. Brad's mother has made every opportunity available to him. He seems to have no job, yet he travels to Peru and Tijuana, owns a car, spends all day doing whatever he wants. He does nothing, ultimately. The answer to the titular question, "What have ye done?" could well be "Nothing." Brad is a disappointment.

So in the two shots that illustrate Brad's turn from reality, we can say that he has turned from reality because he doesn't have the ability to face it. To face reality would be to accept that he must commit himself to a vocation, a career, certain people in order to exist in the human world. One must limit oneself in order to be oneself. To be everything is just to be nothing. Brad isn't the only character unable to face reality. The companions with whom he goes rafting are equally unequipped to face reality. Brad correctly tells them the rapids are too dangerous during the rainy season, yet one continues meditating and the other only says, without much thought, that the challenge is why they've come. They know nothing about whitewater rafting, they're not athletic at all. When Brad later tells them he's not interested in their herbal teas and talking to 'Indians' in sweat lodges, we gather that they're New Agers. What could be a better summation of flakey dilettante lifestyle than New Agers, who grasp onto every new self-centered fad until the next one comes along? So they're pampered Californians with lots of time for flakey New Age thought thinking they can just master the rapids. They face the river, which, as Brad noted, is reality; and they die. They leap into a reality they're unequipped to face. Brad, at least, knows he's not equipped to face it and avoids it via retreat into fantasy.

One would think, given some of Brad's more erratic behaviour, that someone would have tried to get Brad help at some point. Yet none in his life are willing or able to face that reality. Brad's mother clearly lives for Brad. One particularly awkward scene shows her bringing drinks into Brad's room for he and Ingrid; she stands in the doorway for what feels like three minutes (it's around fifteen seconds, actually), until Ingrid at last thanks her. She lives to serve Brad and asks for gratitude only. She also still sees Brad as a child, to the point that of attempting to spoon-feed him. In that particular dinner scene, Herzog frames the shot so the window opens behind Brad and Ingrid, but the curtain covers the outside behind Brad's mother. If Brad has a whole world of opportunity for himself and is unable to commit, his mother has stripped herself of the world through her obsessive devotion to Brad. Their madnesses mutually feed off each other.

If Brad is a crude but accurate caricature of my generation, a generation of people unequipped to face reality, Brad's mother is equally a caricature of the problem, parents who live for their children and give them endless opportunities but no direction, no demands. (And those parents, in turn, are a product of a whole history of Western, materialist culture, which Lee Meyers might call our "Tantalate House.") Direction is what Brad lacks, his energies considerable but uncontrollable. Hence the importance Brad puts in the play The Eumenides. Lee Meyers, the play's director, is literally giving Brad direction. Meyers is the only character in Brad's life who has any sort of control over him. Meyers's relationship with Brad is vaguely fatherly as well: he's affectionate and spends more time with him than his job requires. Although Meyers actually kicks Brad out of the play for being disruptive, Brad calls only Meyers and Ingrid before committing the murder. Clearly they have mutual respect. Unable to distinguish between fantasy and reality now, the direction of the play becomes his direction in life. He has a sense of destiny, killing his mother an act of necessity and fate. After killing her, he casually tells a detective who is unaware he's the suspect, "Razzle them, dazzle them, razzle dazzle them." Life and performance, reality and fantasy, have been conflated. He claims to hear the voice of God, which warned him of the danger in Peru; but as soon as he's barricaded in his home, and immediately--in the film's time--before the key flashback, he tosses "God" (a container of Quaker oats) out of the house saying he no longer needs God. As soon as his 'performance' is over, he's again without direction.

The film concludes with the victory of reality. The first shot of the film is a train driving through a field, on its way to San Diego. The train's motion is rhymed with that of the river. The final shot is of San Diego traffic flowing by behind a basketball in a tree (so placed by Brad). The flowing traffic is like the flowing river and the flowing train: reality rushing on. Inability to face reality doesn't make it go away. The police surrounding Brad's house are a part of that reality, impinging upon Brad's existence in his mother's uterine, pink house whether he likes it or not. Brad has no choice but to eventually meet the reality they represent in some form.

Of course, the film shouldn't be over-intellectualized. Much of it is felt and not quite understandable, much as Brad is not quite understandable and the murder is not quite understandable. The inability to rationalize is a part of encountering the film. The music, for instance, is sombre, sorrowful, and seemingly out of place with the images, producing uncomfortable dissonance. Herzog's decision to make his actors sometimes freeze also produces discomfort as we wonder why they've stopped, yet are clearly blinking. Sometimes they even look directly into the camera. Much of the film's oddness seems present primarily to keep us in a state of confusion, Herzog's use of film form complementing the content so that the mystery of human behaviour and the problem of knowing becomes characterized in the very style. Herzog's camera movements are hypnotic, always moving slowly and gracefully in steadicam, reminding one of some shots in Touch of Evil (the detectives are named Vargas and Hank, coincidentally). So hypnotic are the movements, that I've become drowsy each time I've seen the film. These soporific qualities, the confusing weirdness, leave us as lost as Ingrid and Hank (who are not privy, as we've seen, to the film's key flashback) and all the more disarmed for the jarring moments when Brad explodes. This is only skimming the surface, a brief brainstorming session: Herzog's style in this film could and should be investigated in much more depth.

That Brad McCullum would be a monster for Herzog is no surprise. Considering Herzog's films are famed for their depictions of monomaniacal men, who are quasi-heroes of Herzog's films, a man unable to devote himself to anything as Brad McCullum is monstrous. Herzog focuses on one brief obsession in McCullum's existence, but its brevity and the ease with which it's forgotten make him a model of what Herzog doubtless despises. That Brad is a monster for us has more to do with his unpredictability. As there is no explanation, no good reason, for Brad's behaviour, predicting it is impossible. This keeps not just other characters like Ingrid and Lee on edge, but also the viewers. Though we already know his crime, Michael Shannon's intensity and conviction in every insane line and gesture makes McCullum frightening to behold. Shannon has shown himself to be one of the best actors in America with his performance in Bug, able to put total conviction in the silliest lines, deep menace in the most banal lines. In My Son, he is not nearly so histrionic, his performance more subtle, but the more frightening for it.

I've seen My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? four times now and it's only improved in my estimation each time. Yet, strangely, my perception of it changes with each viewing. The horror of the film struck me the first time. The second time, the comedy of it. Much of what happens in the film could just as easily be humourous as disturbing, or both at once. The last time I was struck with sadness, the film's title encapsulating it. The title is the final words Brad's mother utters when she's stabbed, words gently chastising, yet overwhelmingly sad: this woman who has lived her life for her son and is moved to tears by his gratitude has her life taken away for no good reason. The film's mysteries remain, perhaps magnified, and so does my obsession with it; I think I'll watch it another four times.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? (2009)

Author: Jared Roberts

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment