(This essay contains spoilers. Watch the films first.)

The Jeepers Creepers films concern a monster known as 'The Creeper.' The Creeper 'sleeps' for twenty-three year stretches, then emerges for twenty-three days to 'feed', namely upon humans. I really like The Creeper. He's easily one of the most interesting monsters in modern horror film cinema. If we delve into what makes him so interesting, we'll also discover what makes the Jeepers Creepers films more than just fun monster movies; they're also works of art.

The first thing notable about The Creeper--before we ever notice he's a monster--is that he drives a truck. This first point is curious enough. Very few, if any, horror film monsters proper (i.e. physical creatures of non-human nature) drive vehicles. They attack, push, turn over vehicles; but they don't drive them. Driving a vehicle is a learned human activity, involving developed skills and knowledge. Just how far The Creeper's skills and knowledge go is demonstrated in his ability to terrorize the brother-sister protagonists of the first film. The brother, Darry (Justin Long), comments that his assailant is driving some sort of 'souped-up' truck. And indeed, it does appear The Creeper has some knowledge of mechanics, enough to 'soup-up' his truck. But by far the most remarkable thing about his truck is the false vanity plate reading, 'BEATNGU.' That's "Be eating you!", perhaps a play on The Prisoner's "Be seeing you!", telegraphing to the victims he terrifies on the road that he'll be devouring them later. Not only is The Creeper a skilled driver and mechanic, but he also has a keenly perverse sense of humour.

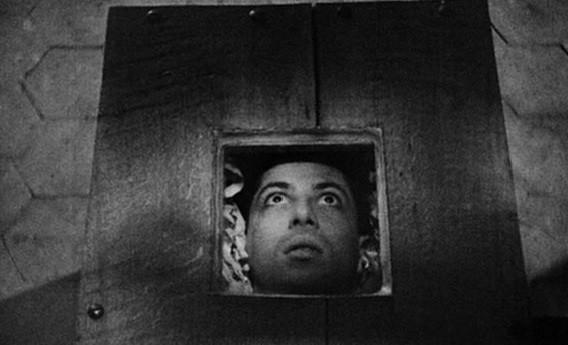

This isn't simply an attempt to mislead the audience in the first half of the film. While it does lead the audience to expect a human villain, subsequent developments suggest a greater significance to The Creeper's humanoid traits. After their encounter with The Creeper on the road, the siblings turn back to the house, actually a church, where they saw The Creeper disposing of bodies down a pipe. When Darry enters the pipe, he finds an elegant, arched subterranean lair where the walls and ceiling are covered with patterns of wax-preserved, stitched-together corpses. At one point in the series, this is described as a horrific approximation of the Sistene Chapel. To be compared to Michelangelo is pretty high praise. However horrific and ghastly the creation, it is indeed very inventive and, in a perverse way, beautiful. This aspect of The Creeper's lair has its effects as far as horrifying the audience goes, but it also shows us The Creeper is an artist. The idea Salva is developing as the narrative reveals more about The Creeper is the monster-as-artist, the possibility for something Other to be capable of creation, not just destruction.

Historically, in monster movies, the monster is a particularly non-creative force. Nosferatu's/Dracula's advances on Lucy are only capable of adding her to the legions of the undead. The Mummy's only imagined union with his chosen woman is, similarly, eternity in living-death, not both alive but both mummies. Frankenstein's monster depends upon his creator, the baron, to make him a woman with whom to live in permanent non-productivity. Creativity is reserved for the living and the 'normal'. Anything monstrous can only destroy. King Kong never builds anything, but he destroys plenty. Dracula, the Mummy, and Frankenstein's monster all take lives. The same applies to the Creature from the Black Lagoon, Romero's zombies, etc.. The rule in horror cinema is that the monstrous cannot create, but can only destroy. The body that conforms to the norm alone is capable of creation.(1)

Given such overwhelming consistency, one wonders why monsters are always represented as inherently destructive. One of the more interesting answers to this question comes from Linda Williams. In her famous essay "When the Woman Looks," she argues that "the monster's power is one of sexual difference from the normal male...the feared power and potency of a different kind of sexuality..." Williams argued that the monster and the female were bound together in their shared otherness from male, phallic sexual power. Since only phallic power can beget, then the monsters are inherently non-creative. However, most of the monsters are male. King Kong, Dracula, the Mummy, the Creature, and Frankenstein's Monster all wanted women, and they wanted, presumably, to fuck those women. That doesn't seem to be a very different sexuality from mine at all! I, too, would have wanted to fuck Fay Wray and Zita Johan in their prime. The sexual difference between the monster and a heterosexual adult male's is that his would be productive and the monster's would not. The monsters, as I pointed out above, consummate their sexuality not in the creation of new life, but in death or violence of some form. So what we can conclude, tweaking Williams's ideas, is that monsters are monstrous not in their sexual difference but in their sexual sterility. (This is more consonant with James Whales's ideas anyway, particularly as presented in The Old Dark House, in which the insane family occupying the house is distinct from their guests in their totally non-productive family form.) They seek relationships that are inherently non-productive and, in the conservative mind, non-productivity is equal to non-creativity.

What Victor Salva does with The Creeper, while he is solidly within the history of traditional horror film monsters, is acknowledge that non-productivity does not preclude creativity. The Creeper is a monster that bears no offspring and is a cause of death and destruction, but he's also an artist. He's such an active artist that one wonders when he takes the time to create his art. If he only has twenty-three days awake to do his artwork on top of all the killing he has to do, then he's a very fast craftsman. Perhaps his twenty-three years of sleep gives him a lot of time for creative thought.

The second film in the series, in which The Creeper targets a busload of high school football players, elaborates further on The Creeper's artistic nature. His weapons are all carved from bone, wrapped with skin, and inlaid with teeth. The Creeper's eye for detail is such that he purposely chose the tattooed skin on Darry's abdomen for the centre of his shuriken. We also see a knife with elaborate scenes carved into the bone handle. But by far the most interesting aspect of The Creeper elaborated in the sequel is his method of feeding, which is itself creative.

The Creeper's 'feeding' isn't performed for the same biological purpose as animal feeding. The Creeper terrifies his victims, smells some odor given off from them while afraid, and by doing so determines which of his victims have particularly choice body parts. When he captures and kills his victims, he doesn't consume the body part and absorb its nutrients as animals would; rather, he assimilaltes the body part whole. In the sequel, The Creeper removes one boy's head and transforms it into his own. He does the same with Darry's eyes in the first film. What's interesting to me about this behaviour is that The Creeper is not just creative, but self-creative. He's able to be an artist of himself by composing his own body out of body parts he finds the most attractive (for reasons unknown to us). The only unchanging body parts are the arachnid-like structure on the back of his head, resembling a face-hugger from the Alien franchise, and his wings. The arachnid creature is, presumably, the 'naked' Creeper, which assembles its body from choice parts. What The Creeper does in this assembly is create its own identity, its way of representing itself to others. Its identity comes not from the point-of-view of others defining it by its difference or monstrosity, but from its own positive self-defining meeting the point-of-view of others.

Jeepers Creepers is not the first of Salva's films to contain this theme. Salva's first feature, Clownhouse, is also concerned with monstrous creativity of a sort. Clownhouse concerns a group of psychopaths who escape from confinement, put on clown costumes, and terrorize a group of children, one of whom is particularly afraid of clowns. We scarcely get to see the escaped psychopaths as themselves. What we see is them invading the clown tent at the circus and applying cosmetics, creating their own identity, as it were. They use creativity to create their identity as scary clowns. They also take a twistedly creative approach toward terrorizing the film's children. Jeepers Creepers just expands and deepens the theme, transforming the psychopaths to a genuine monster and the craftlike creativity to artistry.

It is difficult to take this discussion further without bringing in biographical details on writer-director Victor Salva. Ordinarily biography is best left out of criticism, either because it's speculation read into the film or it's simply not enlightening. In the case of Salva, I think it is both significant and enlightening. Salva, while making Clownhouse, sexually abused the twelve-year-old star and videotaped it. He was reported, tried, and served his jail time. Ten years after Clownhouse, he finally got to make another feature. He even got to make a film for Disney, Powder. This film was boycotted and resulted in protests instigated primarily by the victim, by then an adult, and his family. Each film he's made since has met with some protests by people who believe a convicted pedophile should never be allowed to work again.

That's as much as need be said for our purposes. What we see is that Salva is what is often referred to in our society as a 'monster.' Anyone who abuses a child is 'monstrous'. Perhaps, however, his alternative and distinctly non-productive sexuality (homosexual and pedophilic) is part of what suggests a 'monster' to our society. While I have heard Roman Polanski called a monster very rarely, I have heard it frequently used for Salva. Polanski, despite sexually abusing a twelve-year-old girl, has had wives and has two children with his present wife. Salva, who also sexually abused a twelve-year-old, has never been married and has no children. The difference is one of productivity.

So, like The Creeper and so many other classic movie monsters, Salva is non-productive. But like The Creeper and unlike so many other classic movie monsters, Salva is highly creative. In an interview, he refers to his films as his children. (2) This is very important, because creativity for Salva is allowed to substitute--perhaps very satisfactorily--for productivity; this is true both in his life and in his films. So with The Creeper, Salva is representing a very interesting aspect of who he is: a (social) monster who is also creative, a monster who is an artist, creating darkly beautiful art and creating himself in the process. Seeing the monster-as-artist in the film means seeing the possibility of artistic creation as a substitute for biological creation, artistic creation as a means of recreating oneself: in his films, Salva creates himself insofar as he shows us he is not a monster, but a creator of a different order.

As an amusing turn-of-the-tables, the denouement of Jeepers Creepers II shows the film's major protagonist, a father (Ray Wise) whose child was taken by The Creeper, charging kids to view the sleeping Creeper nailed to a wall of his barn. What's interesting about this is the total lack of creativity in the father's sideshow moneymaking. He's productive enough: he had two children and still has one. But he can only display the Creeper, a self-made work of art, rather than make his own art. Why should biological creation without artistic creation be any less monstrous than artistic creation without biological creation?

But I promised that delving into biography and how Salva reflects himself, the creator of perverse art, in The Creeper would be enlightening. Finally, I want to address this. What seeing the film's relationship to Salva himself makes us ask is just what the protestors of Powder never asked themselves: why can't the monster's art be accepted, even if we don't accept the monster? The Creeper, of course, has to kill to make his art. The Creeper is biologically a monster. But Salva doesn't and isn't. His 'monstrosity' is social only and in creating his art he can also recreate himself. He kills no-one in the process and as I've argued, and am clearly convinced of myself, Salva's films have merit as works of art. There is a possibility of separating moral concerns about the creator from the aesthetic concerns of the created art. Perhaps some are afraid that accepting the monster-as-artist means failing to see him as a monster any longer, failing to see a non-procreative creativity as monstrous.

The Jeepers Creepers films are not masterpieces. They succeed very well as entertaining monster movies, the first being particularly skillful in audience manipulation and the second containing some fantastic monster-slaying action. As penetrating works of art, they are occasionally vapid or confused. The homophobia subtext of the second film is particularly striking as such. It is in the character of The Creeper, a character into which Salva has clearly invested much of himself, that the films show great depth and insight about human concerns of monstrosity and art, and their possible co-existence. (3)

(1) There are, of course, apparent exceptions. Science-fiction horror films tend to rely, in fact, upon the horrible productivity of the monster. The Alien films in particular feature the horrific chestbursters, alien young bursting from the human bodies in which they've been implanted. Inseminoid, as the title implies, is about nothing other than an alien force that impregnates human women. There is, too, a large body of cinema--both animated and live-action--in Japan in which demons and/or aliens capture, rape, and impregnate busty human women. The most fruitful argument to deal with this objection is that in these films the very productivity of the aliens itself, which uses rather than complements human creativity itself is destructive and repulsive. It's production through destruction rather than creation. But that argument must wait for another essay.

(2) "Interview with Victor Salva," by Mike Gencarelli, www.mediamikes.com. Sept. 24, 2011.

(3) Jeepers Creepers III has been conceived and I am eagerly awaiting its birth to see how well it meshes with the ideas explored in this essay.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

Monstrous Creativity: Jeepers Creepers I (2001) & II (2003)

Author: Jared Roberts

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comments:

Thanks for this analysis. I definitely think you are on to something. When I first saw Jeepers Creepers in a movie theatre, alone, I was freaked the fuck out precisely because I was aware of Salva's past. I definitely think he created this movie to address and acknowledge his own impulsive pedo desires. At the same time, I think he is playing on cultural anxieties and fears of sexual predators to make a movie that gets under everyone's skin. Not a perfect film, as you say, but definitely honest. Most frightening of all, I read that last image in the last scene, of Darry's decimated shell, eyes plucked out, as Salva's final assertion that he is still the monster, but now he has the power to make films, and as his Creeper looks back at us through Darry's shell, with Darry's eyes, I think it is directed at the boy (now man) who sent him to prison -- and Salva admits that the monster still lives in him . . . and is hungry.

Post a Comment