The opening credits roll over a beautiful, blond woman--whom we never see again--caressing herself and masturbating in a luxurious and artfully lit bed. We then plunge into action: a man runs frantically through the city, shrieking in terror at the sight of any woman--all of whom appear to him as growling, grey-faced demons--ultimately leaping to his death to avoid contact with the woman trying to rescue him; at the same time a child is born; the paramedics ushering the child into the world try to help a saintly woman who has been randomly stabbed, but fail; as she dies telling the paramedic she loves him, another woman in the hospital suddenly rises from her deathbed and, using a fire extinguisher, murders a couple mid-proposal; the paramedic returns home to find his wife in mid-coitus with another man. That's all in the first eighteen minutes of Evil Angel. Never has a film quite so strongly and cosmically immersed itself in its thematic core so immediately, except perhaps for 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Evil Angel, the latest picture from ex-King of Mormon Cinema Richard Dutcher, is clearly about women. To be more exact, it's about how men relate to and perceive women, from a decidedly male and decidedly sexual point of view. As much as Feminists will insist that thousands of years of Patriarchal domination has allowed the male point of view limitless expression, that's not entirely true. If the Feminists are correct, they should be the first to realize that no gender can be accurately or authentically represented in such a system. The male point of view has never been allowed an expression of vulnerability and fear in the face of female sexuality. The way society has been constructed, a woman need only wink at another man to deeply wound her husband emotionally, psychologically, and socially. On equal grounds, where we can all tell the truth about ourselves, a male point of view is perhaps something quite new. Evil Angel stands in awed confusion and terror of female sexuality. But most importantly, it has a lot of fun doing it.

The story of Evil Angel is based on the Lilith legend of Jewish folklore. According to legend, Adam's first wife was not Eve but Lilith. Lilith demanded equality, symbolized by her refusal to take the bottom position in sex, and flew away dejected when Adam insisted he be on top. Adam then got his submissive Eve and Lilith committed herself to making miserable the children of Adam. So the themes of female-male relationships, particularly of equality and loyalty within those relationships, is built into the very legend from which Evil Angel is derived; Dutcher exploits that fully. It wouldn't be a stretch to say the whole film is a struggle to see who's on top, in this case emotionally and socially, but through sexual overpowering.

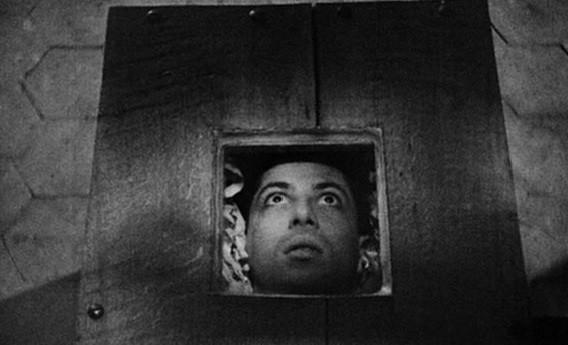

Lilith's mechanism is something like Azazel's in Fallen (1998); she's a spiritual being who can take over bodies. Azazel could take over any body, male or female, human or animal. Lilith only takes the bodies of sexy women and can only enter them when they're temporarily dead. After she commits a few murders, a private investigator (Ving Rhames) whose son has become one of her victims starts to put the pieces together. Meanwhile, Marcus (Kristopher Shepard), the paramedic, deals with his suicidal wife, Carla (Ava Gaudet), and his obsession with the saintly stab victim he tried to save. These two narrative strands lightly intersect when Carla's suicide attempts leaves her temporarily dead.

There are a few subplots running throughout. The plot is, in fact, a series of criss-crossing subplots. A major subplot is Marcus's research into the life of Emma, the saintly woman. The first time he sees her, gasping for life with multiple stab wounds, he feels connected to her. The more he looks into her life, reading her journals and talking to her priest, the more he discovers that she is indeed the perfect woman in his mind. His wife is emminently imperfect. He finds her with another man. It's important to note, as well, that she's on top. His best friend, a beautiful young paramedic, is in love with him, but he's not interested. He himself says the first time in his life he's really fallen in love is with a dead woman, Emma. Her journals reveal that she's conformed herself to a thoroughly Catholic mould of femininity, refusing her sexual urges until she finds the right man and living to serve others. To Marcus, she's the ideal wife. Carla is alive and so free to continually disappoint him; Emma can remain an ideal, untouched by the realities of human existence. Emma is easy to love because she's not real and never can be; she is, in short, his Eve. That makes his wife Carla his Lilith, the woman he rejects for her overstepping her sexual bounds and virtually diminishing his sexual potency. Carla is thus prime material to literally become Lilith, as she does.

Lilith's personality, if it can be called such, is wholly infantile, a "blind drive to annihilate those toward whom [she] feel[s] anger, to force satisfaction from those who stimulate [her], to wrench food for [herself] if only by devouring those who feed [her]."(1) With Lilith, the emphasis is certainly on the 'blind drive to annihilate' part. If she were purely and directedly misanthropic, she'd presumably just use a body to become a world leader and launch a nuclear war. She's neither disciplined nor interested enough to do that. As the legend stipulates, she is Resentment Incarnate. She feels anger toward men, toward happy couples, and toward any situation of women conforming to male standards. In one of her bodies, for instance, she works as a prostitute and purposely spreads HIV to her clients. Under the guise of wanting a starring role, she lures gonzo pornographers to a secluded place just to kill them. These are all instances where men, arguably, exploit women sexually; at least, as far as Lilith is concerned, women are too submissive in these contexts. There's something wrong, for her, with the very notion of giving men pleasure, unless it's to hurt them later.

One wonders if Dutcher had had a few arguments with militant Feminists before he wrote Evil Angel. It sometimes seems as though Lilith stands in for the whole of Feminism, which can be and has been (e.g. by Harold Bloom) seen as essentially resentful. But Lilith is not always so ideologically directed. She kills the mother of one of her previous bodies, as well as her boss from another body, for no other reason than bubbling hatred. Just as she enjoys the pleasures of life, like sex and drugs, manipulation and deception, she seems to enjoy destroying those toward whom she feels anger. There's not much else to her. As evil as she is, she's so inventively and relentlessly cruel that we almost grow to like her as we do a Freddy Krueger.

As with all true art, Evil Angel provides no answers, but only investigations. The attitudes toward women on display are not intellectual points that could have been written in an essay--not even this one, really--but a matter of the sentiments, constructed more emotionally than intellectually. Dutcher seems to be working out a lot of conflicting attitudes toward women and toward men's attitudes. On the one hand, he's dubious of traditional standards for submissive women. Marcus is clearly presented as naively, even ridiculously, traditional, not to mention necrophiliac, for his obsession with the dead saint. A position that villainizes women for not conforming to that standard is chastised by the film. Yet the film has an accusatory feeling, pointing a finger at female sexuality. Lilith is a succubus. She dominates through sex. She gets on top psychologically and socially by getting on top sexually. The men of the film are mostly kind, almost too kind. Marcus is a very sweet man who, throughout the film, has his whole life destroyed by his relationships with women he trusts. He is deceived and hurt every step of the way. Very little of it is his fault. Clara, albeit not an entirely unsympathetic character, is somewhat monstrous even before Lilith gets to her. Moreover, the private investigator, in another subplot, paternally tries to rescue a young woman (Jontille Gerard) from a life of prostitution. Both men are gentle and kind, certainly not deserving of Lilith. In some sense, the legendary Adam is an unmentioned character, symbolizing perhaps a whole history of patriarchy that created Lilith. So the essential confusion at the heart of the film is that female sexuality is an object of horror, because it makes men vulnerable and can hurt them, while at the same time viewing it as an object of horror is treated as, if prudent, also priggish, antiquated and part of the problem.

Also worthy of note is Dutcher's editing techniques. During the first half of the film all events seem to be linked in synchronicity. For instance, when Marcus reads one of Emma's journal entries about her father, Dutcher intercuts scenes of the private investigator dealing with the death of his son. There are several such cuts, often involving three lines of action. The action is unified only by ideas, commenting upon one another and revealing unspoken emotions, but never impacting one another directly. In fact, one of the most shocking aspects of Evil Angel is Dutcher's sleight-of-hand in offering what appear to be cliche narrative moves that turn out to be anything but cliche. Threads that appear certain to connect, to reach certain destined points, run off in new directions or are suddenly cut short in gleefully macabre ways, a sort of violence to the tropes as much as to the characters. As the film runs on, the synchronous editing style tapers off. I initially thought this was in service to the plot, much as Paul Leni's editing tricks in The Cat and the Canary taper off after the first twenty minutes. But it's possible Dutcher did this intentionally, giving the impression of narrative fraying, synchronicity coming apart, destiny denied.

This editing style leads into the strange nihilism in Evil Angel. The essential problem is articulated by one of the characters. If good souls go to enjoy a heaven and evil souls like Lilith can enter bodies instead of going to a hell, that is to say, if the good die young and the evil live on indefinitely, there seems to be a fundamental disorder in the world. The way obvious connections aren't met, the way cliches are intentionally denied to shock us, increases the nihilistic impression, the feel that the universe is a cruel universe where good things don't always work out, good intentions aren't always rewarded, and good people don't always get the happiest of endings. Nowhere is this nihilism so strongly realized as in the relationships between men and women. The one sign of hope is that perhaps, should Marcus survive, his encounter with Lilith may just have been what he needed; he would be freed of his Eve delusions and his depressing wife. And she may be what we the audience needed. Maybe she leaves us, men and women, a little wiser about ourselves and free to start anew. For men, perhaps it's cathartic to see an archetypally evil female the target of violence; for women, perhaps to see a dominant female sexuality render men nearly powerless.

Whatever nihilistic and anti-feminist worldview Dutcher may have been working out through his screenplay, his playfulness was certainly not affected. We're invited to laugh at and with this cruel world and its inventive monster. Dutcher clearly relishes the freedom to have as much perverse fun with his camera and narrative as he wishes. Apart from the clever editing, there's also some fun with mise-en-scene, as when ornamental swords are slyly removed and restored to a scene background, with grim jokes, and with camera angles and movements (which I sadly can't detail since the film is yet to be released on DVD). Often such a stylish picture has weak acting, but Dutcher's cast, most of whom have very few prior film credits, is excellent. Ava Gaudet is exceptional, adeptly portraying the depressive Carla half the film and the manic Lilith the other half. The real gem performance, however, is Jontille Gerard in her small supporting role as the young prostitute, exhibiting considerable emotional range. Stylishly shot, well-written, and original, Dutcher has made a horror film that's both very fun and thoughtful in Evil Angel.

1. Carol J. Clover. "Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film." 1987.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

Evil Angel (2009) - 4/4

Author: Jared Roberts

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment