From the first moments of The Human Centipede, when the sinister Dr. Heiter (Dieter Laser) is looking at photos of his beloved Three-Dog--three rottweilers sewn together anus-to-mouth--and when some vapid, American club-girls are lost and arguing in the German woods, it's clear it is not a film about characters reconnecting with lost childhood or a subtle narrative that will ultimately leave one wondering "Who is the human centipede really?" Human Centipede is dedicated to its gimmick. It stands or falls on how effective, affective, and significantly that gimmick is used. As it happens, the gimmick is used quite well.

The gimmick is the creation of a totally human monstrosity, which is the human centipede, three humans sewn together anus-to-mouth. While the monstrosity is an abomination, a loathesome and aberrant thing to the sight, to the mind, due to its physical implications, it is a piteous creature for which we feel sympathy. The real monster of the film is the perverse urge to create the monstrosity--by the mad scientist and by the writer-director, Tom Six. It is a gimmick that resembles and derives some significance from Frankenstein (1931) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), later mad scientist pictures like Les yeux sans visage (1960) and most recently The X-Files: I Want to Believe (2008). In each of these films the urge to create using human flesh as one's medium, a creativity that uses science for macabre art rather than any practical function and doesn't ask permission for its creation, is the source of horror.

Science is collaborative and functions within an ethical context of response. One doesn't take, nor does one give, a body part without permission. Art, however, is totally autonomous. These mad scientists all present themselves, consciously or unconsciously, as artists rather than true scientists. They guard their creation until it can finally be revealed in its beauty. Frankenstein is horrified to find his monster wasn't beautiful. Dr. Genessier of Les yeux is horrified to find his daughter's new face rotting off. Dr. Heiter's position in this tradition is an interesting one. He isn't horrified by his monstrosity. He loves it. He sees it as a pet. When parts of it aren't quite working according to his satisfaction, his solution is simply to replace one part with another. Perhaps it's just that Heiter is madder than any other scientist in cinematic history. Frankenstein's experiments have a purpose. He wants to creative artificial life and in doing so can discover what the essence of life is. The medical benefits are innumerable. Dr. Genessier wants to restore his daughter's face. If he succeeds, however, his research could have great benefits for the world. He'd certainly deserve a Nobel prize. The mad scientist of The X-Files wants to give his lover a new body. There's really no good reason for Dr. Heiter's creation. It is pure, mad creativity. He seems to just find the idea amusing. It's something he wants to try. Perhaps he just wants to see what will happen. Perhaps he just wants it as a pet in a totally infantile way. Certainly the way the film explores Heiter's interaction with the monstrosity is one of master to disobedient pet.

Consequently, there is no way to forgive Dr. Heiter. There is forgiveness for Dr. Frankenstein. He's a good man and a good scientist who just went, not too far, but too far alone. He stood outside of the scientific and moral community to create his biological artwork. A scientist observes ethical concerns and works within a community. Had Dr. Frankenstein done so, the monster could have been in a controlled environment. That he repents his errors is key to his forgiveness. He is even the hero of the films. Dr. Genessier is forgiveable primarily because we can understand his love for his daughter, though his experiments are still ghastly transgressions. He doesn't wait for face-donors: he steals faces from beautiful girls. Dr. Heiter is also outside the moral and scientific community, he also steals, but there's no way to forgive him. Unlike the other scientists, he is not a good man. He is apparently a renowned surgeon, but somewhere along the way, he clearly lost his mind. Or perhaps he only became a surgeon as part of a plan to create a human centipede. We never find out because, as I say in the first paragraph, the film isn't interested in character study. What we do find out from Dr. Heiter is that he hates human beings. Converting them into an insect of sorts is only too appropriate for him. He's a total, malevolent sociopath. His closest parallel for pure madness is Malita in The Devil-Doll (1936), but he exceeds her in malice by far. Malita wants to shrink everyone as an inexplicable act of revenge for her husband's death. She doesn't particularly hate humans as Heiter does.

Like Frankenstein and Les yeux sans visage, Human Centipede is structured around its experiment. The first act is collecting the parts. In Frankenstein, this consisted in collecting bodies. In Les yeux, Alida Valli is sent out to lure and incapacitate young women. Heiter's version is shooting with tranquilizer darts anyone who stops along the highway to defecate. The second act is creating the monstrosity. Though not nearly as poetic, the creation scene of Centipede resembles Les yeux most of all. In Les yeux, Georges Franju quite controversially for 1960 (one critic called the film "the sickest film since I started film criticism") chose to show the face transplant operations as realistically as he could manage, the scalpel cutting delicately around the eyes, the face peeling off and revealing bloody muscular material beneath. Centipede does the same. Dr. Heiter is shown cutting flesh, the lipidous material hanging in flaps. The third act is observing the monstrosity and preparing for its revolt. The fourth act is the revolt and the struggle to either destroy or correct the monstrosity, while outside forces begin closing in: the villagers with torches, or, in the case of Centipede, the police.

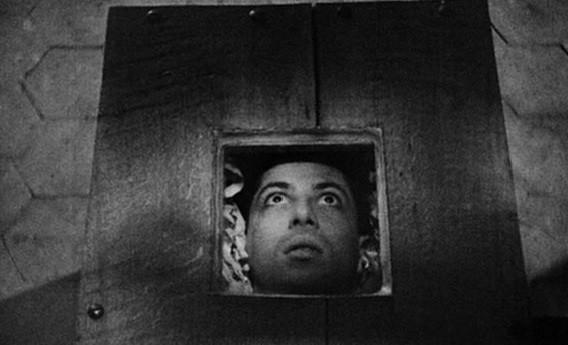

The strength of Human Centipede is in the third act. The other acts have their degree of tedium. Since the gimmick of the centipede is the heart of the picture, seeing the centipede in action is where the picture is at its most powerful. Tom Six is willing to explore the centipede's sad existence farther than many filmmakers would, but he could have and probably should have gone farther still. He does explore how eating and defecation works; how they must cooperate merely to walk; what they are expected to do for the doctor, and so forth. However disturbing it is, there is a very dark comic edge to this act. One scene in particular, in which Dr. Heiter tries to train the centipede to bring him his daily newspaper like a dog, is particularly played for humour. I couldn't help but be amused by Heiter's reactions. He is so over-the-top and so naively evil in these scenes he is grimly and, for the audience uncomfortably, amusing. The successfully conflicting emotions of this very memorable section of the film owes quite a bit to the brilliantly dark performance of Dieter Laser is the doctor.

The misanthropy of Dr. Heiter sets the general theme and tone of the picture. From Heiter's collecting victims mid-defecation to his sewing them in such a way that their are defecating into one another's mouths to his decision to make them into the shape of a centipede, there is a clear disgust with human bodily existence on display. While we watch, we are not disembodied. The bodily plight of the monstrosity made me uncomfortable in a physical way. We feel a certain disgust with our bodily existence that unites us with the disturbing content of the film and makes us identify very uncomfortably with Heiter as much as with the centipede. Heiter's creation of an insect out of humans has Greek resonance. How many myths consist in Greek gods transforming humans to insects? The mad scientist as god theme compliments the misanthropy, viewing these average, normal humans as insects. The one man in the centipede, and very patriarchally the one person with a mouthpiece, eventually calls himself an insect for his misused life. The girls are certainly not model humans. They're not bad people. They're just normal. They like going to clubs, dancing, drinking. The majority of humans have such low demands for themselves. Since Heiter dominates the film, the tone that dominates the film is that these people's lives have been selfish and base. Perhaps the most poetic moment in the film is when we discover that, while the man is willing to defecate, the middle girl refuses. One needn't be selfish. In such a tightly-woven collective, one has to make sacrifices. In fact, insects are extremely cooperative, so the metaphor is rather awkward; but that's not very relevant. The film does attain a certain poetry when the centipede learns to cooperate, a sort of perverse, fleshy Argo.

I've probably made a stronger case for the themes of The Human Centipede than it actually deserves. Their appearance in the film is sporadic and somewhat confused. It's never clear whether Heiter's attitude is totally condemned, whether he has some moral value. For that matter, the inability to derive nutrition from fecal matter and the fact that all three parts of the 'centipede' retain their own brains, make the experiment itself somewhat confused. The real strengths of Human Centipede are the disturbing science, its gimmick, which is to say, its monstrous creation and of course its monstrous creator, easily one of the maddest of all cinematic mad scientists, Dr. Heiter. Heiter and his experiment certainly did disturb me and clearly intrigued me. A good gimmick explored thoroughly can indeed produce a good film. The Human Centipede a fascinating picture.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

The Human Centipede (2009) - 3/4

Author: Jared Roberts

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

You should be doing reviews for the New York Times, your intellect and infusion of artistic nuance is engaging and exacting, and executed brilliantly!Geraldine Winters

Gee, I wish you were on the hiring committee at the New York Times. Thanks for the kind words.

Cheers!

Post a Comment