As a relatively little-read internet reviewer, I question the wisdom of writing about the Twilight series. What can I have to say that hasn't been said? I don't care to wade through all the internet literature on Twilight; I can only hope I, as an impartial outsider, have some fresh insight to contribute. For my part, writing about the films will satisfy a need to express just why, despite not being the target audience, I find these films so fascinating. ("These films," incidentally, refers to Twilight, New Moon, and Eclipse.)

The gist of the series is as follows. Bella, a fairly normal albeit melancholic and diffident teen girl in her senior year of highschool, returns to her hometown to live with her father. While fitting in with the normal students, she's drawn to the strangely contemptuous and pallid Edward. Soon they fall in love and she learns he's a vampire. The complication comes from Jacob, a childhood friend with whom she also falls in love and who happens to be a werewolf. Throughout the films Bella learns about both vampire and werewolf society and of the antipathy between them. She realizes she's not being fought over by two attractive young men, but by two whole societies. To choose one is to preclude herself from the other. The indecisive Bella dicks both men around for an inordinately long time and causes both conflicts and truces between the societies as she does so.

What most interests me about the films is Bella's dilemma. I suppose that's what interest teenage girls as well, but for different reasons. I'm fascinated by her dilemma because of what it represents, namely, class conflict. The vampires have extremely white skin, traditional nuclear family structure (despite not being related to one another), high education, elegant clothes, a spotless and modern-design mansion, and impeccable manners. The werewolves, in contrast, all have tanned skin, a loose and shifting family structure (follow the character Leah), trade learning (motorcycle repair), wear nothing but shorts, live in wood cabins, and often roughhouse.

The contrast is between what Nietzsche classed as Apollonian and Dionysian impulses; between cultured life and natural life (i.e. the Noble Savage). Cultured life has always been seen as high class and natural life low class. On the other hand, as in Rousseau, cultured life is seen as phony and natural life truer and purer. These prejudices have been in place as long as human civilization. There are certainly virtues to both 'sides', if indeed it's necessary to have sides. Cultured life can be seen as too secondary, detached from lived experience; too effete in situations that really count. A library science scholar is useless in a survival situation; a mechanic isn't. However, sophistication has attractions: artistic and poetic beauty, deep conversations, romance and comedy.

The sexual implications, however, are at the forefront of Twilight. The sexual implications of the class distinction is, as in Twilight, centered upon the men. Women are supposed to, and often do, want men who are aggressive, muscular, tough, good with their hands, often sweating and getting dirty--"manly" men. On the other hand, they like men who are romantic, poetic, witty, and intellectually stimulating--cultured men. The men who are of the "manly" variety are made to feel inadquate for their lack of refinement; the refined men are made to feel inadequate for not being manly enough, as though culture is feminizing. (The arts are oftened considered 'sissy' stuff by the uncultured.) Hence the depiction so often found in Hollywood of a woman who marries a cultured man then has an affair with a brawny, working-class man. The lower class is seen as good for sexual stimulation, the upper class as good for intellectual stimulation. (It is on this prejudice that the whole of interracial pornography seems to thrive.) Bella's position in the film is in choosing between the two ends of the spectrum women desire: men who can be wild and men who can, as Shakespeare put it, word them.(1) Edward can word her; Jacob can thrill her.

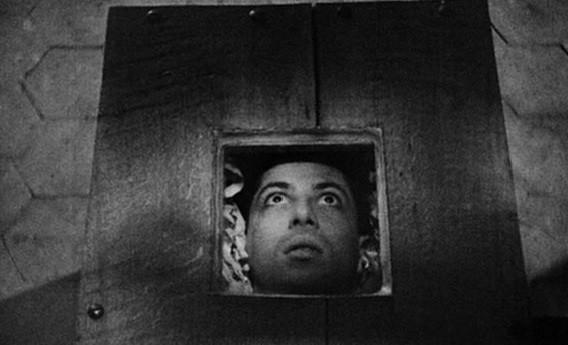

This distinction is represented faithfully in the films. Edward is always seen as having to restrain his passion (his desire for her blood), Jacob is always free to express his passion. Where Edward has graduated from school countless times, as he's perpetually 17, Jacob spends his time roughhousing and cliffdiving with his fellow shirt-allergy sufferers. (McConaughey and Danzig would make good werewolves.) The most revealing scene, presented so chastely for the teens of course, is when Bella is being kept safely on a frosty mountain. While she freezes in the tent, the undead Edward, whose body produces no heat, is unable to keep her warm. Jacob, however, produces more body heat than the average human. So he has to slip into bed with Bella to warm her while Edward sits, observing. That's the distinction in a nutshell: hot/cold in bed, good/bad with words, restrained/unrestrained emotions.

Of course, the distinction is objectionable to men. Cultured men are not incapable of being wild lovers or aggressive fighters; 'uncultured' men are not incapable of being poets or sensitive lovers. What is unfortunate about the Twilight Saga is that it never provides an alternative. Rather than suggest that this dichotomy is unnecessary or an illusion created by over a century filled with penny-dreadful romance novels, soap operas, and pandering movies, Twilight takes us into the mind of a girl who is indeed choosing between the sides and never learns how erroneous that is. A bildungsroman Twilight is not. The progress is not interior; it is merely exterior. She chooses and that is all. To be fair, Edward, at least, does not fit his stereotype; he is able to thrill her in between his sullen, soft-spoken speeches. Also to be fair, Bella herself is choosing between the individuals as individuals, not as archetypes.

While both individuals Bella has to choose from are admirable. It would be difficult for any woman to really find either Edward or Jacob anything less than desirable. Both are very handsome young men; both are very sincere and loyal; both are a teenage girl's dream come true, albeit in different ways. Bella's insistance on keeping both men on a leash while she chooses thus makes her a rather unpleasant character. One might argue that Jacob is a puppy that doesn't give up. Rather, he's a practical man who needs to be given a clear and straight-forward denial, which is not forthcoming from Bella. She prefers to keep him around so she can dangle in front of him like a carrot, leading him to do whatever she wants but giving nothing in return. Edward, on the other hand, she keeps closer, but frequently humiliates when she wants to make sure Jacob doesn't leave her grip and thus throws him a bone. Why either of these genuinely nice young men want anything to do with her is puzzling to me.

But it's just a girl's fantasy. I'm taking a fantasy too seriously. The films are and must be seen as the fantasies of a girl as she daydreams on a rainy day, listening to indie rock on her iPod. The dream is of two implausibly attractive and generous young men fighting for her; of whole cultures fighting to protect her, because she's the fairest princess in the land. Because this is her fantasy, it doesn't matter if she's kind of a bitch. Because this is her fantasy, we can set aside the realism and just enjoy it for what it is. Hopefully girls who fantasize this way will grow up and learn that real people can be so much more than cultured and wildman archetypes.

The events of the series that are not directly concerned with Bella's dual love are caused by it. An evening game with Edward's family attracts the attention of some renegade vampires. The rest of the series deals with the repercussions. Both vampire family and werewolf family strive to protect Bella for the sakes of their smitten members. This results in some conflicts between the families and some temporary truces. Bella's interference with the cold but cease-fire relationship leads to a perhaps more amicable peace. I would like to relate this to the class-conflict issue discussed earlier, but I can't, except as a dream of risible optimism. The point is that a shared love unites classes and cultures. But of course, all people do love and long for the same things and it hasn't worked yet.

Each film manages to include some fantastical fight scenes. These are enjoyable for their kinetic and aggressive qualities. Vampires can take and deliver punches that are just impossible in real life. In other words, the fights are very much descendents of The Matrix's fight scenes. Either you like this sort of fight choreography or you don't. Personally I prefer traditional, Jackie Chan-style fights; but there's undeniably quite a lot of enjoyment to be had in seeing a werewolf tearing a vampire to pieces.

What isn't fun is the constant posing. Before a fight, after a fight, and sometimes randomly, the characters, usually the vampires, will strike book-cover style poses. The artificiaility is cloying. Nobody randomly poses in real life. And I don't remember it being the plight of vampires to randomly strike poses. It's an artifact of the filmmaking, allowing poster-shots mid-film. The results are silly and tedious.

Overall, the series is surprisingly entertaining. They are indeed geared for a female audience, a girl's fantasy. But girls fatasize much as men do. Men fantasize about fighting for girls; girls fantasize about being fought over by men. Our fantasizes couldn't be more compatible. We still have fights, love, sex, suffering, more fights, and more love. So choose a side and dive into the fantasy. I chose Edward, if you must know.

(1) "He words me, girls, he words me." Antony and Cleopatra, 5.2.

Help make this site more interesting through discussion:

The Twilight Saga - 3/4

Author: Jared Roberts

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment